The Kintsugi Strategy: Mending Political Fragmentation

You can't unsmash a pot, but with Kintsugi you can repair it in a way that honours its history, golden welds transforming it into something beautiful while acknowledging the trauma of its fractures.

In the traditional Japanese art of kintsugi, broken ceramics are transformed. With golden joins, new stunning seams tell the story of the scars. The mended pot is even considered more beautiful than before it was broken. Can we use this philosophical approach to heal our fragmented society? If collapse is inevitable, is it even worth trying?

In political science, 'political fragmentation' is when the division of the political landscape splits in so many ways that governance becomes inefficient and eventually impossible.

Caveat

Political fragmentation is one of the precursors of collapse that I identify here, and I consider it inversely proportional to Stoic Cosmopolitanism. However, nothing I would suggest to solve political fragmentation should be mistaken or misconstrued as a justification for appeasing Fascism or accepting hate. They are the pot smashed. Not part of the process of repair.

The Metaphorical Cup

"If, for example, you are fond of a specific ceramic cup, remind yourself that it is only ceramic cups in general of which you are fond. Then, if it breaks, you will not be disturbed."

Epictetus

In his analogy of the broken cup, Epictetus gently introduces the idea of building resilience to loss through perspective - with the idea of a favourite cup being smashed. He then extends this principle to more significant losses, such as of a loved one. That jump can feel jarring on a first reading.

His lesson is that loss and destruction are inevitable, but there is still room to choose how to react. But we have one planet and, currently, one Global civilisation. If it smashes, what comfort is it to think it was only of planets in general that we were fond of?

Kintsugi, (Lit. Golden Joinery) is a Japanese method of mending smashed ceramics and allows us to explore the metaphor further. In a world where striving for unattainable perfection stresses us, Kintsugi offers a different perspective of embracing imperfections. We can use it to consider not just how to avoid being derailed when the cup is smashed but how we can pick up the pieces and influence what happens next.

An object cannot be separated from its history - including its breaks and repairs. By highlighting the cracks with gold, we can transform them into something beautiful and unique. The beauty in the breakdown lies in the acceptance and celebration of imperfections.

Four Philisophical Pillars of Kintsugi:

Resilience

"I can be changed by what happens to me. But I refuse to be reduced by it."

Maya Angelou

Kintsugi embodies resilience. Even after being broken, something can be made whole and even more beautiful. We can overcome adversity, loss, and emerge stronger.

Acceptance

"Your scar is an important part of your life and is a part of you. It is a living history; never look at scars as negative, instead take it as positive."

Shawzi Tsukanoto

Kintsugi encourages us to accept imperfections in ourselves and the world around us. Instead of hiding our flaws, it suggests embracing them as part of what makes us unique.

Transformation

"Kintsugi is based on the belief that something broken is stronger and more beautiful because of its imperfections, the history attached to it, and its altered state."

Jo Ann V. Glim

Kintsugi highlights the transformative power of adversity. Broken pottery is transformed into a work of art. Our struggles can shape us into more compassionate and resilient individuals. There's beauty in the breakdown.

Wabi-sabi

"Nothing lasts forever, nothing is complete, nothing is perfect."

Shawzi Tsukanoto

Kintsugi embodies the aesthetic of wabi-sabi. Finding beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and simplicity.

Understanding Political Fragmentation

I'm publishing this article now because of the fallout from the US election - but it could equally apply to Scottish Independence, the UK on Brexit, or Nationalist and Unionist Northern Ireland.

The Pew Research Center on social sciences publishes comprehensive studies on political polarisation in the United States. It provides in-depth analysis and data on how American political attitudes and values have shifted, illustrating the increasing ideological divide between Democrats and Republicans. Pew researches various factors influencing political identities and party alignment, including demographic changes, educational differences, and media consumption habits.

Continental Drift

Their findings consistently show that the partisan gap has not only deepened but also solidified over the past few decades, affecting everything from policy preferences to social attitudes.

In the US, the two-party and presidential system can lead to the idea of polarisation being a simple dichotomy, but fragmentation goes way beyond this.

In the UK, similar divides have been presented as binary divisions over the past decade, with Two-party races and Two-option referendums. For example, polarisations on constitutional matters such as Scottish Independence and Brexit - the vote to leave the European Union.

In isolation, these can make it seem like society is polarised into two homogenous and nearly equal 'halves'. This narrative drives' them and us' tribalism.

In 2014 Scotland voted to remain in the UK 55% to 45% to leave.

In 2016 UK voted 52% to leave the EU 48% to remain.

But look what happens in Scotland when those votes are layered on top of each other in the analysis.

This is not 'polarisation into a dichotomy'. It is fragmentation. The first thing we should note is the implication for democracy. There is no democratic majority position on a basic building block of a community as the Constitution.

No matter what the result of the dichotomy votes of referenda were: most Scots would be unhappy with it. Despite the vote results, there is no majority view.

Now imagine laying other attitudes on top of this. Gender ideology. Immigration, Climate Change… Suddenly, you have 8, 16, 32 different demographic 'tribes'. How can so many overlapping groups with fundamental areas of disagreement make up a coherent society?

Societies with the appearance of coherence have similar divisions; however, in 'normal' times, people do not define themselves by them. People compromise. People live with the differences. Now, these differences are being deliberately wedged wider by authoritarian nationalists. Weak autocratic leaders may prefer less fragmentation as there are fewer threats; Strong Authoritarians who have solidified their position may prefer a highly fragmented environment, as all potential opposition is weaker.

In the UK, the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) publishes research similar to Pew's in its "British Social Attitudes Survey". The latest British Social Attitudes survey shows the UK is becoming increasingly politically fragmented, fueled by economic and social upheavals.

The survey points to deepening regional splits, particularly in opinions on government roles and economic inequality. Efforts like the 'levelling up' initiative have done little to shift perceptions of the north-south divide. Trust in government and politicians has plummeted to unprecedented lows, marred by scandals and mishandling of Brexit and the COVID-19 aftermath.

More people in the UK now back proportional representation, moving away from the traditional first-past-the-post voting system. This signals frustration with the status quo in politics. First past the post is meant to create a stable government; what it's actually creating is results where often most people are unhappy, and many votes don't count at all. The difference is between results where one party has a majority and results that require cooperation or coalition.

A relatively straightforward left-right spectrum traditionally dominated the UK's political landscape. The Brexit referendum unveiled and manufactured deep-seated divisions around economics, core values, and beliefs regarding freedom, governance, nationality, identity, and societal control. That means the UK now grapples with a libertarian-authoritarian divide that is breaking political alignments and influencing voter behaviour - and which Professor Curtis's results say is now a long-term feature.

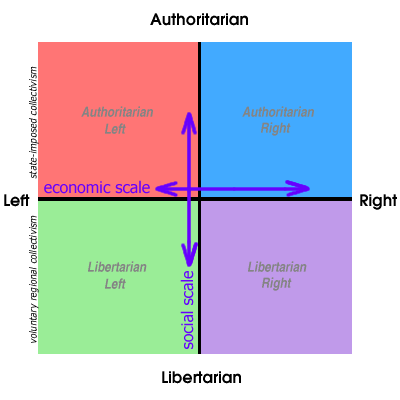

The Political Compass

That libertarian-authoritarian divide complicates the political narrative, demanding that democratic governance somehow address and integrate various ideological currents into coherent platforms.

Any model is doomed to be a gross oversimplification. The political compass represents the two dimensions as a grid - that authoritarian and Libertarian are on the social scale and Left/right are economic. It's helpful, and I recommend taking the test, but it's not perfect.

The Temptation of Nationalism

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.Wilfred Owen

For many, Nationalism appears to be the answer. Touted as a means of unity, with appeals to patriotism. However, Nationalism is inherently, by definition, divisive; it pits cousins, communities and countries against each other.

Forty years of failed climate treaties reveal a bleak truth: economically competitive nation-states are fundamentally limited in their ability to address collective crises, as each nation prioritises short-term economic gains over long-term global survival.

Nationalism requires you to take an invisible line on a map, and use it to define people as "us" and "them" - it is a denial of a common humanity.

The same logic and artificial divisions apply if your tribe is a gender, a race, or even a class.

Man-made climate change-driven collapse will not respect man-made borders.

This political fragmentation is one of the precursors of the collapse we identified. It might be inevitable, but we understand how it grows and harms us - so we can suggest several strategies, backed by Psychology, Sociology and Economics, that can act as our Golden welds.

Golden Welds of Praxis

Bridge Social Ties for Resilience

Cultivating resilience, individually and within communities, is the foundation of countering fragmentation. Building resilient communities is essential for societal stability. Sociologist Robert Putnam's research highlights the critical role of social capital—networks, norms, and trust—in enabling effective collective action towards shared objectives. Putnam distinguishes between 'bonding' social capital, which connects like-minded individuals within a tribe, and 'bridging' social capital, which connects diverse groups, offering broader perspectives and access to varied resources.

These connections are vital in building a resilient community, as they enhance democratic governance and community welfare by knitting together a strong fabric of civic, social, associational, and political life.

When political structures falter, communities fortified with bridging social capital can serve as the bedrock of survival and progress. When communities are fractured, making these bridging social ties are golden welds.

These bridging mends help communities share resources, skills, and responsibilities, strengthening individual well-being and bolstering collective action. However, communities must remain vigilant against the breaking - the scapegoating propagated by nationalist demagogues in times of crisis.

Build and Maintain Cross-Group Alliances

Studies in conflict resolution show that alliances across different political or social groups reduce hostility and build empathy. These are the 'bridging' connections Putnam argues are so critical. Creating intergroup initiatives—such as neighbourhood improvement projects, environmental clean-ups, or volunteer work—brings people together around shared community goals rather than divisive issues. These activities create collective purpose, reduce prejudice, and help people see each other as allies rather than rivals.

It can seem impossible, but I've seen it happen.

Martin McGuinness and Ian Paisley, figures once emblematic of Northern Ireland's deep-seated sectarian divisions, charted one of the most unlikely political alliances in recent history. I had very little time for either of them or their views. McGuinness - an IRA commander, and Paisley, the firebrand leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, epitomised the hostility and distrust that fueled decades of conflict known as 'The Troubles.'

Martin McGuinness was a terrorist leader, ordering murders, handling weapons and setting indiscriminate bombs.

Paisley was a bigoted firebrand politician linked to funding for terror groups such as the UVF. They were the embodiment of the troubles I grew up with.

Yet, in a turn of events that would once have seemed inconceivable, they came together to co-lead Northern Ireland's government following the 2007 St Andrews Agreement.

As First Minister and Deputy First Minister, their governance marked a critical phase in the peace process, steering Northern Ireland away from its fractious past towards a shared future. The animosity that had once defined their relationship transformed into an unexpected camaraderie, earning them the nickname "The Chuckle Brothers."

Their frequent public displays of warmth and mutual respect became symbolic of the new era of cooperation between unionists and nationalists, illustrating the possibility of reconciliation and partnership even amongst the most bitter of adversaries.

As an aside - I've not had that many conversations with Nuns, but one nun I did strike up a conversation with ( I was bored at work, they were doing a charity collection, I brought them in for a cup of tea) picking up on my accent, was telling me she thought Ian Paisley was a very good constituency MP for all his constituents regardless of their religion or politics.

Develop Platforms for Open Dialogue and Collective Decision-Making

Creating spaces for open, non-partisan dialogue within communities encourages civil engagement and mitigates fragmentation. Evidence from deliberative democracy studies shows that communities are more likely to reach a consensus when they have structured opportunities to discuss local issues.

Community-led forums, town halls, and local councils where people can voice concerns and collaborate on solutions strengthen social bonds and allow for constructive expression of diverse perspectives. Putnam puts down a division in modern America directly to the loss of these shared community forums.

Localised Economic Initiatives

Economic self-reliance at the local level reduces dependence on national and global systems, which are more vulnerable to political and economic instability. Cooperative initiatives like community-supported agriculture (CSA) schemes, mutual aid groups, and local business cooperatives create a buffer against broader economic instability and encourage community cohesion. Studies indicate that economic stability at the community level can increase social trust and reduce tensions driven by competition.

It's better for the environment too. A closer connection to your food and having a person and a known face in the supply and purchase of goods and services directly influences our perception of community interdependence while lowering food miles.

Promote Media Literacy and Critical Thinking

One of the most potent tools against divisive narratives is critical media literacy. Research shows that people are more likely to believe misinformation when they lack the skills to evaluate sources critically

Access to media literacy programmes, especially within educational institutions and community centres, can empower individuals to identify bias, question sources, and resist manipulative media tactics. Workshops, online courses, and resource-sharing effectively nurtures a critical, informed community.

Media literacy is the ability to access, analyse, evaluate, and create media in various forms. It helps individuals become more discerning consumers and producers of media. Techniques for enhancing media literacy include:

Checking the credibility of sources.

Recognising biases.

Comparing information across different sources.

Questioning the purpose behind media messages.

The SIFT technique is one way to reduce the vectors of this and misinformation.

The technique is a ‘Four Move’ method designed to help individuals quickly evaluate online information and combat disinformation. The design is to stop people from sharing fake news. It consists of four steps:

Stop: Pause before engaging with or sharing a piece of information. Consider whether you know the source and whether it's trustworthy. This prevents impulsive reactions to potentially misleading content.

Investigate the Source: Check the credibility of the source. Look up the author, publication, or organisation behind the information. Reliable sources typically have a history of accuracy and transparency.

Find Better Coverage: Look for other reputable sources that cover the same topic. Cross-referencing multiple sources helps confirm accuracy and identify potential biases.

Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to Their Original Context: Follow links or citations to find the original context of the claim, quote, or image. This helps avoid being misled by altered, cropped, or out-of-context information.

By applying these steps, individuals can critically assess the reliability of online content, avoid falling for false claims, and contribute to a more informed digital environment. Teaching skills like these encourages critical thinking and empowers people to navigate the complex media landscape effectively and responsibly.

Combat Disinformation

Disinformation is a driving force behind political fragmentation, and community-level efforts to counter it can be highly effective. Initiatives that engage trusted local figures—such as teachers, librarians, and community leaders—can disseminate accurate information and model fact-checking behaviours. Research shows that communities are less susceptible to polarising narratives when local leaders champion accurate information and equip people with tools to verify facts. Social media groups devoted to debunking falsehoods and promoting verified news can be crucial in building resilience to misinformation.

This isn't foolproof. Yes, social corrections, such as fact-checks or flags labelling news as false, are effective at reducing belief in and engagement with false news. When people see these corrections, they are less likely to perceive the flagged content as accurate or interact with it by liking, sharing, or commenting. This makes social corrections a helpful tool for combating misinformation. However, they are not without risks.

The exact same mechanism can backfire when trustworthy news is incorrectly flagged as false. In such cases, trust in accurate information decreases, and people are less likely to engage with it. This undermines confidence in reliable sources and belief in legitimate news overall. Importantly, this effect is not influenced by factors such as how strongly the correction is presented, individuals' distrust of experts, their critical thinking abilities, or their susceptibility to social influence. So while social corrections are valuable for addressing falsehoods, they must be applied carefully to avoid damaging public trust in credible information.

Strengthen Civic and Environmental Education

In-depth civic education helps citizens understand governance, recognise manipulation, and make informed choices. Environmental education, similarly, highlights shared responsibility and global citizenship, encouraging people to view climate and ecological issues as collective, not partisan, concerns. Studies show that communities with strong environmental awareness are more likely to act cohesively in the face of ecological challenges as they understand the interconnectedness of their actions.

Education level has a significant impact on voting patterns.

We see this in the recent US election

https://www.nzz.ch/english/us-2024-voting-patterns-by-the-numbers-ld.1856257

And in Climate Change:

And there is a clear correlation between education and the Brexit vote too:

Cosmopolitan Values and Empathy-Based Perspectives

Adopting a cosmopolitan worldview helps individuals and communities transcend nationalistic divisions and appreciate shared human values. Empathy-based approaches, where people are encouraged to view others' experiences as interconnected with their own, reduce divisive mindsets. Research supports that when individuals develop a sense of "global citizenship" and empathise with diverse cultures, they are more likely to engage in pro-social behaviours that benefit the community as a whole.

Cosmopolitanism advocates a world where loyalty to humanity overrides loyalty to nations or political factions. In practice, we should develop deep connections within our local communities rather than focusing on national allegiances. These bonds provide practical resilience and reinforce a shared identity, reminding people that our fates are intertwined. This approach draws on sociological research, which shows that local solidarity, especially in crisis, significantly improves communities' capacity to adapt and endure challenges.

Cosmopolitanism has roots in ancient proto-Stoic and Stoic philosophy, where it was seen not just as a theoretical ideal but as a disciplined way of life. For the Stoics, the concept of cosmopolis—a world city or global community—embodied the belief that every human belongs to a larger order that transcends political boundaries and cultural divisions. This worldview held that each individual is part of a shared moral and rational order, a concept famously articulated by the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, who taught that we are all "citizens of the world." By embracing cosmopolitanism, Stoics advocated for an ethics that prioritised universal human welfare over narrow tribal loyalties.

The Stoic practice of cosmopolitanism goes beyond merely tolerating others; it requires an active commitment to the well-being of all people, regardless of national or social ties. Marcus Aurelius frequently reflects on this duty in his Meditations, emphasising that each person's actions should benefit the whole. He writes,

"What isn't good for the hive, isn't good for the bee"

(Aurelius, Meditations, 6.54),

This underscores the Stoic view that individual happiness is deeply interconnected with communal welfare. By cultivating a cosmopolitan mindset, Stoics aim to rise above petty disputes, grounding themselves in principles that create social harmony and mutual understanding.

Practically, Stoic cosmopolitanism encourages the practice of empathy and self-control as essential to bridging divides. Stoic cosmopolitanism encourages individuals to imagine themselves in the place of others, a technique known as sympatheia, which builds compassion and a sense of shared destiny. This perspective teaches that personal concerns, whether over comfort or material gain, should be balanced against the needs of humanity. Stoics advocate for cultivating a "universal sympathy", a compassionate perspective of empathy that reduces social discord and urges each person to act in ways that promote the common good.

Cosmopolitanism as a Stoic practice is inherently practical and resilient, especially in the context of societal collapse. By grounding individuals in a universal ethical framework, cosmopolitanism builds a mental resilience that helps people weather uncertainty without retreating into divisive or exclusionary mindsets.

The Stoics understood that crisis often drives people toward tribalism or reactionary thinking, as fear fuels distrust and hostility. Yet, as Marcus Aurelius emphasised, a cosmopolitan approach allows us to remain level-headed and avoid the impulsiveness that fragmentation and collapse can breed. This mindset helps communities to remain open to cooperation, even in the most trying circumstances, as they act in alignment with shared human values rather than the reactive, defensive instincts that arise in times of hardship.

In this way, Stoic cosmopolitanism becomes not just a moral imperative but a survival strategy, cultivating the psychological and social strength that communities need to adapt to collapse. By reminding people of their interdependence and shared humanity, cosmopolitanism offers a grounding perspective that reduces the appeal of conflict-driven ideologies and encourages the cooperation essential for resilience. The Stoic commitment to cosmopolitanism thus not only serves as a guiding ideal but as an actionable framework for building a more compassionate, united, and enduring society amidst crisis.

However, while Stoic Cosmopolitanism makes us consider the whole, we can act where we are and with those who are in our immediate community. The praxis of this means acting with the value of mutual aid to build resilient, interconnected communities with reciprocal support.

We can see spontaneous mutual aid in response to crises like natural disasters, they can be effective in mobilising resources - and can build bonds across the barricades that last after the disaster. Well, we are in a Global crisis, and it isn't going away.

The Myopia of Utopia

To repair the smashed pot, you need to be able to identify the cracks clearly. The divisions fracturing us — reinforced by self-interested parties acting on a 'divide and conquer' —are short-sighted and meaningless in the face of the real, shared, imminent threats to our existence. But just because the divisions are meaningless in the face of an apocalypse does not mean they are not real. There are people who would rather the pot stay smashed if they can't form it in the shape they want.

Society is becoming more divided on many important issues, affecting how people talk about them and how politics works worldwide. Populists are fermenting nationalist tensions about identity - creating scapegoats and blurring people's ability to see issues at a Global level. Racial inequalities highlight unfairness in justice, healthcare and education systems globally. Gender rights are also a hot and divisive topic, with movements pushing for gender equality and trans rights facing both advancement and pushback. People have very different opinions on how much the government should be involved in sharing wealth and managing markets. Religious beliefs have always split communities and affect social policies and government decisions.

Climate change is the most damning point of contention, with environmental advocates urgently calling for action while many in power or profit remain sceptical or in denial.

These divisions in values and beliefs are being made worse, often on purpose, by misinformation, a polarised media landscape, and deliberate misinformation and disinformation.

Kintsugi is a philosophy of embracing flaws and imperfections, viewing them as valuable parts of the story, not just blemishes to be concealed. Our societies are fragmented. Smashed and swept into different piles.

We can't unsmash the pot.

Think of that diagram of quartered constitutional attitudes on Brexit and Scottish Independence in the UK. Whatever the result - even delivering the plurality that 28% want - leaves most people unhappy.

Democracy with political fragmentation means that most people are unhappy about most issues all of the time.

There is a danger of increased instability here. The re-election of incumbents is inversely proportional to perceived voter satisfaction.

Two factors are acting against stability - increased fragmentation leaves more voters unhappy, but also - as we approach collapse, things will tend to get worse over time faster than new governments and control can act against them - so even with the most competent governance, voters will be worse off than they were at the last point in the electoral cycle, opening the field for less competent usurpation. The loss of incumbent advantage can mean more frequent and extreme swings in power transfers as the system breaks down.

We can only try to slow or undo this process by implementing kitsuige-inspired practical, evidence-backed measures. If communities can strengthen social cohesion, we can counter the forces driving political fragmentation. In an increasingly polarised world, these steps offer a means to build a foundation of trust, shared purpose, and resilience that can withstand even profound systemic pressures.

We can't unsmash the pot, but maybe we can mend it back better: or at least help it hold water a little longer.

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Ghosh, I. (2019, September 25). Charts: America's Political Divide, From 1994–2017. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/charts-americas-political-divide-1994-2017/

Curtice, S. J. (2024). BSA 41: One-dimensional or two-dimensional? The changing dividing lines of Britain's electoral politics. National Centre for Social Research. Retrieved from https://natcen.ac.uk/publications/bsa-41-one-dimensional-or-two-dimensional

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: W.W. Norton.

The Political Compass. (n.d.). https://www.politicalcompass.org/

Retrieved November 17, 2024, from

Fishkin, J. S. (2018). Democracy When the People Are Thinking: Revitalising Our Politics through Public Deliberation. Oxford University Press.

Golosov, G. V. (2018). The five shades of grey: Party systems and authoritarian institutions in post-Soviet Central Asian states. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 9(2), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2018.1500442

Irvine, W. B. (2009). A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy. Oxford University Press.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the "Post-Truth" Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353-369.

Stoeckel, F., Stöckli, S., Ceka, B., Ricchi, C., Lyons, B., & Reifler, J. (2024). Social corrections act as a double-edged sword by reducing the perceived accuracy of false and real news in the UK, Germany, and Italy. Communications Psychology, 2, Article 10.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(7), 2521-2526.

UK Government. (2006). The St Andrews Agreement: October 2006. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-st-andrews-agreement-october-2006

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.