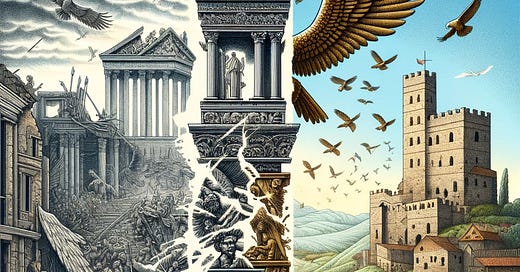

Debating the State. What is the Best Form of Government? (Part II - Fall into Feudalism)

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century set the stage for the emergence of feudalism. Largely discounted now, but are there benefits to such a system?

In "What is the best form of Goverment" part 1, I looked at ancient answers from the Western tradition - Greece and Rome.

First, I want to address my own biases and shortcomings. I write about a mix of what I know and what I'm interested in, and in political history terms, that broadly means the Bronze Age and the classical world from Myceneans through to the fall of the Western empire and then Neo-classical Renaissance through to maybe late C19th. That's not to say I'm not interested in pre-history, Mesopotamia, the Celts, The East, The Vikings, The Normans, the rest of the world or medieval Europe, or that I see no value in them. But I need more confidence in context to write about them. If someone mentions "The Dark Ages", my mind first goes to the Bronze Age Collapse!

Writing from a constitutional Monarchy, feudalism played as big a part as the classical world in shaping the Europe I grew up in. The "decline and fall" of Western Rome was not a singular event but a gradual process influenced by various factors, including economic troubles, military pressures from outside invaders, and internal political instability. I look at this more closely in "A Beginners Guide to Collapse." The once-mighty empire, which had efficiently governed vast territories, had a collapse in complexity, leaving a power vacuum in its wake.

Emergence of Feudalism: A New Social Order

Transition from Roman to Feudal Governance

The transition from Roman to feudal governance represented a shift from a centralised bureaucratic state to a more fragmented and localised system. Where the Roman Empire had a complex administrative and legal structure, feudalism relied on personal relationships and local authority. This decentralisation was partly a response to the challenges of governing vast areas without the administrative mechanisms or technology that the Romans had developed.

In the ensuing chaos and uncertainty, feudalism took root as Europe's dominant social and political system. Feudalism was more than a government structure; it was a comprehensive social system that strictly defined economic, political, and social relationships. In some ways it was a timocracy - rule by land ownership.

Key Features of Feudalism:

Hierarchical System:

At the top of the feudal hierarchy was the monarch, followed by nobles and knights, and at the bottom the peasants or serfs. This hierarchy was underpinned by a system of obligations and duties that bound each level to the others. This can be compared to Rome with its orders of plebs, eques and senators and grades of slaves, freemen and citizens.

Land Ownership and Control:

Land was the primary source of wealth and power. The monarch granted large estates or fiefs to nobles, who in turn could parcel out smaller portions of these lands to knights in exchange for military service.

The Manorial System:

The economic foundation of feudalism was the manor, a self-sufficient estate controlled by a noble. Peasants worked the land in exchange for protection and a place to live. They were tied to the land, unable to leave without the lord's permission.

Military Service and Knighthood:

Knights, often minor nobility or warriors of lower rank, were granted land in return for military service. They theoretically upheld the chivalric code, which combined martial prowess with ideals of honour and duty.

Vassalage and Allegiance:

Feudalism was characterised by a web of allegiance and service. A vassal pledged loyalty to a lord in exchange for land and protection. This relationship was formalised through ceremonies where oaths of fealty were exchanged. This was more formal than the client-patron arrangements of Rome.

The Role of the Church:

The Church was a central and unifying force in feudal society. It held vast tracts of land and played a vital role in the governance and legal systems. Bishops and abbots often acted as feudal lords.

The essence of feudalism lay in its reciprocal relationships; lords provided land and protection to their vassals, who, in return, pledged loyalty and military service. This network of mutual duties fostered a sense of order and predictability, vital in an era rife with uncertainty and conflict. Also, feudalism was instrumental in upholding chivalric and martial values, cultivating virtues like honour and bravery, which still significantly influenced European culture and ethics.

The Darkness in the Ages

The Dark Ages are not as dark as they are often painted; however, the flip side of feudalism revealed a system riddled with inherent inequalities and injustices. Most of the population, primarily peasants and serfs, endured a life of limited rights and freedoms, anchored to the land they worked on. This perpetuated a rigid class system, stifling social mobility and nurturing a landscape of inequality.

The localised nature of governance led to political fragmentation, often resulting in conflicts and hampering a unified response to external threats. Economically, feudalism's agrarian focus limited the scope for development and innovation, as the emphasis remained on subsistence rather than growth or exploration. The system's resistance to change and deep-rooted conservatism further hindered progress, making it resistant to new ideas and technologies.

In defence of feudalism, some argue that it provided essential structure and stability during tumultuous times. The mutual obligations and social fabric it wove were necessary for survival in an unpredictable era. On the other hand, critics of feudalism highlight its role in entrenching social inequalities and suppressing personal freedoms. They point out that the system's emphasis on hierarchy and tradition often perpetuated outdated practices and hindered societal and economic progress.

While it offered order and stability in a time of chaos, it also reinforced social inequalities and economic stagnation. Feudalism laid much of the groundwork for medieval Europe's political, social, and economic structures. It influenced the development of legal and military systems, shaped social hierarchies, and even affected cultural norms and values. The legacy of feudalism can be seen in the modern concepts of land ownership, legal obligations, and the hierarchical organisation of societies.

Thomas Aquinas: The Ideal Governance in Scholastic Thought

We can't skip past Aquinas when discussing this period and thinkers on ideal government. He did not directly address feudalism, but his interpretation can be seen as a link back to Aristotelian thinking, linked to Christian theocracy. I would see this as a step back - where Aristotle was describing how the world could be based on his interpretation of observation of things natural states, Aquinas introduced more of a top-down morality and plan from a deity on how the world should be, and relying on faith.

Aquinas's Vision of Governance

In his "Summa Theologica" Aquinas delves into the nature of the ideal government. His thoughts are deeply rooted in Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology. For Aquinas, the best form of government is mixed, combining elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. This perspective is grounded in his understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of each system.

Monarchy:

Aquinas saw monarchy as the most efficient form of governance. A single, virtuous ruler could provide clear and consistent leadership. However, he was acutely aware of the dangers of tyranny if a monarch becomes corrupt. Thus, while he appreciated the efficiency of centralised administration, he cautioned against the concentration of too much power in one individual's hands.

Aristocracy:

Aquinas also valued aristocracy, where a group of wise and virtuous elites governs. He believed that such a group could provide balanced and moral leadership. However, he recognised the risk of elitism and detachment from the needs of the common people.

Democracy:

Finally, Aquinas acknowledged the value of democracy, particularly its emphasis on freedom and the involvement of the populace in governance. He appreciated the democratic principle that leaders should serve the common good and be accountable to the people.

Synthesis in Governance

Like Aristotle and Cicero, Aquinas advocated for a synthesis of these forms, where the efficiency of a monarch is balanced by the wisdom of an aristocratic council and the participatory virtues of democracy. This mixed form, he argued, would mitigate the risks inherent in each system when taken alone. The monarch provides unity and direction, the aristocracy offers wise counsel, and democratic elements ensure the ruler's accountability and the people's participation.

Aquinas's ideal government is deeply infused with his moral and theological principles. He emphasised that regardless of the form, the primary aim of governance should be the common good, and rulers must be guided by moral virtue and a commitment to justice. His vision of a mixed government reflects a careful balance between authority and liberty, order and participation. Where feudalism relied on a rigid hierarchy, and -as we look at in the next article, Hobbes envisioned a strong central authority to prevent chaos, Aquinas proposed a more nuanced and balanced system that sought to harmonise different governance elements for the welfare of all.

John of Salisbury: The Precursor to Hobbes in Metaphorical Statecraft

Thomas Hobbes' "Leviathan" famously imagines the state as a person, but it wasn't an original metaphor; it was used in a feudal context by John of Salisbury. Writing in the 12th century, Salisbury's "Policraticus" can be seen as a defence of feudalism and predated Hobbes by several centuries.

In "Policraticus" Salisbury presents an intricate metaphor, depicting society as a living organism, a concept that beautifully mirrors the essence of the feudal system. He envisions the state as a body - a body politic. In this vivid analogy, the king is portrayed as the head, directing and overseeing the entire body's functions, symbolising the pivotal role of monarchial leadership in maintaining societal order. The church, described as the soul, reflects the deep intertwining of religious authority with medieval governance, underscoring the church's role in guiding moral and ethical standards.

The various classes of people are likened to different parts of the body, each having a distinct but crucial role. The nobility and knights, akin to the arms, protect and serve the realm. At the same time, the peasants, symbolised as the feet, are the foundation of society's structure, supporting and enabling its movement and growth. This analogy is not merely descriptive but prescriptive, advocating for a structured, hierarchical society where each class has a defined role and purpose and harmonious interdependence.

Salisbury's metaphor is strikingly similar to Hobbes' later depiction of the state as a Leviathan. However, while Hobbes uses the metaphor to advocate for a strong, central authority to avoid the brutish nature of man in a state of nature, Salisbury's focus is more on illustrating the organic unity and interdependence of different societal segments within the feudal framework.

This early conceptualisation of the state as a body prefigures Hobbes' more secular approach, highlighting a medieval understanding of governance. Salisbury's view encapsulates the essence of feudalism – a system where the reciprocal duties and responsibilities between different societal tiers were akin to the interconnected organs of a living body. This organic view of society, emphasising hierarchy and mutual obligations, shaped the medieval worldview and laid the groundwork for later political philosophies, including Hobbes' "Leviathan."

In the next in this series - from Feudalism to Fedralism, We'll look at Hobbes, Paine , Hamilton and the emergence of modern political thought. Subscribe now to get it in your inbox for free!

Brief Overview of Non-Western Political Arrangements and Theories (500 AD to 1500 AD)

The period between 500 AD and 1500 AD saw diverse political arrangements and philosophical developments across the non-Western world. This era was marked by great empires, influential thinkers, and unique political systems outside the European context. I'd love at some point to do a detailed compare and contrast between Stoicism and Indian and Chinese philosophies, but in the meantime, here's a whistlestop tour of what was going on in the rest of the world at the time of Feudal Europe.

Asia

China: This period covers the Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, and early Ming dynasties. The Tang and Song dynasties were particularly notable for their bureaucratic systems and civil service exams, which created a meritocracy. Philosophers like Confucius (551-479 BC, whose teachings continued to influence this period) and Zhu Xi (1130–1200 AD) were significant, with Confucianism profoundly impacting governmental ideals focused on ethics, social harmony, and proper governance.

India: The Gupta Empire (circa 320-550 AD) was a golden age of culture and political stability, succeeded by various regional kingdoms like the Chola and Vijayanagara Empires. Political thought during this period was influenced by texts like the Arthashastra, attributed to Chanakya (4th century BC), emphasising statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy. Hinduism and Buddhism significantly influenced the governance, focusing on dharma (righteousness) and the moral duties of rulers.

Middle East and Islamic World

Islamic Caliphates: Spanning from the Umayyad to the Ottoman Empire, this era saw vast Islamic empires. Key political concepts were derived from Islamic law (Sharia) and the works of philosophers like Al-Farabi (872-950 AD), Avicenna (980-1037 AD), and Averroes (1126–1198 AD). These thinkers blended Greek philosophy with Islamic theology, discussing the ideal state, the role of religion in governance, and the qualities of a good ruler. Not only did scholars in the Caliphate preserve much ancient thought, but they also paved the way for much modern science and mathematics.

Africa

African Kingdoms: Empires like Mali and Songhai flourished in West Africa and Great Zimbabwe in the south. Leadership often combined tribal traditions with Islamic influences (in North and West Africa). Mansa Musa of Mali (reign: c. 1312–1337 AD) is a notable figure renowned for his wealth and the promotion of Islamic scholarship.

Americas

Mesoamerica and South America: The Maya civilisation, despite its earlier Classic period peak, remained influential in Mesoamerica, followed by the Aztec Empire. In South America, the Inca Empire rose to prominence. These civilisations were characterised by centralised solid rule (the Inca emperor, the Sapa Inca, as a divine figure) and intricate social and economic systems, but with less emphasis on individual political philosophy.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

Byzantine Empire: Continuing from the Eastern Roman Empire, it maintained a complex bureaucracy and was influenced by Christian theology in governance. Thinkers like John of Damascus (676-749 AD) contributed to the blend of political and religious thought. They were speaking in Greek but considered themselves Roman.

Mongol Empire: Under leaders like Genghis Khan and his successors, the Mongol Empire's governance was characterised by a combination of tribal leadership and adaptation of the administrative practices of conquered regions. And horses. LOTS of horses.