It's Not Rocket Surgery...

An article claims neurological science says Pit Bulls are predisposed to aggression, to support their calls for banning breeds: But the study wasn't on aggression and only included one Pit Bull.

Anti-XL Bully campaigners are sharing a US article which cites a Harvard neurological study into canine brains as proof that pit bulls are predisposed to aggression to support their calls for a ban and eradication. I examine their claims in light of the original published study. At the heart of this analysis is deflating their assertion that the study, which included only one’ pit bull’ and did not specifically focus on aggression, somehow demonstrates that all pit bulls are inherently too aggressive to coexist with humans. Such a sweeping generalisation demanded a critical evaluation, especially considering the potential consequences for thousands of dogs and their owners.

It Isn’t Rocket Surgery

There is a heated debate in the UK over the recent breed-specific legislation, which is leading to tens of thousands of dogs being caught up in the XL-Bully Ban. For such an emotional subject, we have a duty to make evidence-led decisions. I’ve previously looked here at how research shows breed-specific legislation is not backed up as being effective; in these articles, I’ve referenced and linked to multiple peer-reviewed academic papers - sometimes representing decades of study.

So I am glad for the sake of the debate if anti-breed lobbyists are also referring to peer-reviewed academic papers - however, it’s an issue if they are misleading others by claiming their position is backed by science, when the papers they cite don't show what they claim.

In this article, I look first at the study in question and its findings - then the claims being made so you can decide if they are justified.

The Canine Brains Project

Dr. Hecht, Ph.D formed the Canine Brain Project in 2015. The primary aim of this project is to explore and quantify the neural, temperamental, and behavioural variation across dogs and other canids. This research is crucial for understanding the diverse aspects of dogs, such as their sociality, motivation, emotional reactivity, and prey drive, and how these traits vary across breeds, bloodlines, or individuals.

This project significantly contributes to understanding canine cognition and behaviour, leveraging the expertise and resources of one of the world’s leading universities. I look at the study in question, “Significant Neuroanatomical Variation Among Domestic Dog Breeds”, to ascertain if the anti-breed claims are indeed supported by the scientific evidence.

From what I can understand, they are not, and given their professed love of dogs, I’m sure Dr. Hecht et al. would be horrified at how their research is being misused.

Top Dog Scientists

“We are all dog lovers who do not harm the dogs who are involved in our research.”

The Canine Brains Project

Meet the pack of researchers: Dr. Erin Hecht, a notable figure in evolutionary neuroscience, led the study in question. Dr. Hecht is a highly credible and accomplished neuroscience and evolutionary biology academic. She completed her Bachelor of Science in Cognitive Science at the University of California, San Diego, in 2006, followed by a Ph.D. in Neuroscience from Emory University in 2013. Dr. Hecht currently holds the position of Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, a testament to her expertise and standing in the academic community.

Dr Hecht’s team comprised experts in various fields, including neurology, evolutionary biology, and animal behaviour. Hecht’s primary role involved designing the research, conducting it, analysing data, writing the first draft, and editing the paper.

Jeroen B. Smaers, associated with the Department of Anthropology at Stony Brook University in New York, contributed significantly to the project. He was involved in performing the research, analysing the data, and playing a crucial role in writing and editing the paper. William D. Dunn, from the Department of Neurology at Emory University’s School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, was instrumental in the data analysis phase of the research. Marc Kent, affiliated with the Department of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery at The University of Georgia in Athens, participated in performing the study and was involved in the paper’s editing process. Todd M. Preuss, representing two departments at Emory University in Atlanta—the Division of Neuropharmacology and Neurologic Diseases at Yerkes National Primate Research Institute and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine—was a key figure in designing the research. He also contributed to the editing of the paper. David A. Gutman, also from Emory University’s Department of Neurology, played a significant role in analysing the data and editing the paper.

This collaborative effort, bridging diverse fields and institutions, exemplifies a multidisciplinary research approach, combining expertise from evolutionary biology, anthropology, neurology, and veterinary medicine to achieve comprehensive insights into the study’s objectives, lending significant credibility to their findings.

Methodology: A Rigorous Approach to Understanding Canine Brain Structure

The methodology employed in “Significant Neuroanatomical Variation Among Domestic Dog Breeds” is a testament to the study’s scientific rigour. The research team used Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to study the brain structures of 62 dogs from 33 different breeds. This diverse sample size was crucial for obtaining a representative understanding of the canine population.

Dogs from mixed or unknown breeds were excluded from analyses that used breed group as an independent variable. One “Pit Bull” was in the sample, but pit bull is not recognised as a breed, so was not presented in any of the breed-specific analyses.

The approach was data-driven and agnostic, meaning the researchers did not start with a preconceived hypothesis about breed-specific brain structures. Instead, they let the data guide their conclusions. This unbiased approach is critical in scientific research, particularly when dealing with complex traits like behaviour and aggression.

The study also accounted for various factors that could influence brain structure, such as body size, skull shape, and the phylogenetic history of the breeds. Considering these variables, the researchers ensured their findings were not skewed by external factors unrelated to the brain’s anatomy.

Results: Understanding What the Study Actually Reveals

The results are intriguing and informative. The study found noticeable variations in brain anatomy across different dog breeds. Importantly, these variations were not solely attributable to physical factors like brain size or skull shape but also the breeds’ specific behavioural specialisations.

For instance, the research identified differences in brain regions associated with hunting, guarding, and companionship tasks. This suggests that selective breeding for certain behaviours over generations has shaped the canine brain in measurable ways.

The study does not make definitive claims about ‘aggression’ being a genetically predetermined trait in certain breeds based on brain structure. While it acknowledges the complexity of linking specific neuroanatomical features to behaviours, including aggression, it stops short of directly correlating brain structure and aggressive behaviour in particular breeds like pit bulls.

This distinction is vital because it highlights a gap between the study’s findings and how they are being presented in the context of breed-specific aggression.

The research provides valuable insights into how selective breeding can influence the canine brain, but it does not support the claim that certain breeds are inherently aggressive due to their brain structure or that brain structure is the only or even major, determinative factor above the nine other factors such as socialisation and environment that other behaviourists have identified.

Identifying Brain Regions and Traits:

The researchers could identify variations in specific brain regions by examining the MRI scans. These regions were then correlated with behaviours traditionally associated with each breed, such as hunting, guarding, and companionship.

Sample Size and Breed Representation: The study’s sample included a range of breeds, but it’s important to note that the number of dogs per breed varied widely. This variation means that while the results indicate neuroanatomical differences, they may do not fully represent every individual within a breed, and may not be statistically significant for each breed. The study’s approach focused on identifying trends across breeds rather than making definitive statements about individual dogs.

The extent of Differences Between Breeds: The differences in brain structure between breeds were statistically significant but varied in magnitude. The study found that these differences were not solely due to physical factors like brain size or skull shape, indicating a deeper neuroanatomical variation.

Skull Shape and Brain Functionality: It’s crucial to understand that while skull shape can influence brain shape, it does not directly dictate brain functionality. The study accounted for this by separating the effects of physical brain size and shape from the brain’s functional organisation.

Variability Within Breeds: Dogs of the same breed can exhibit different behaviours, which the study acknowledges. This variability is due to a combination of factors, including genetics, environment, training, and individual life experiences. The study focused on general trends rather than the specific behaviours of individual dogs.

Other Factors Influencing Behavior: Besides neuroanatomical development, the study recognises that several other factors influence a dog’s behaviour. These include upbringing, training, socialisation, and individual experiences. Genetics provides a framework for potential behaviours, but environment and experience are crucial in shaping actual behaviours.

Navigating the Nuances of Canine Neuroanatomy and Behavior

The study represents a significant step in understanding how selective breeding has shaped the canine brain. Their findings reveal that while there are indeed variations in brain structure across different breeds, these variations are complex and cannot be simplistically linked to predict an individual dog’s behaviour.

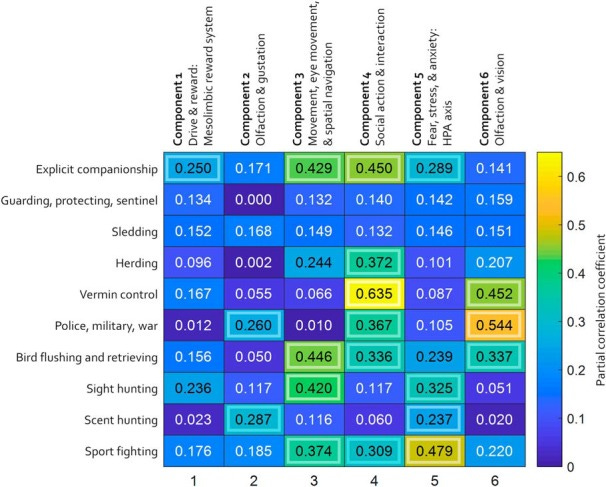

This data visualisation from the study shows how different connected parts of the brain, which change together in shape, are related to the evolutionary tree of various breeds. The circles in the figure represent the strength of these relationships.

This second diagram shows the relationship between brain areas that change in shape and specific behaviours exhibited in the figure. Different colours in the figure show the strength of these relationships, determined through a detailed statistical method. Areas in the figure with outlined boxes are those where the findings are statistically reliable, meaning they are unlikely to be just by chance. Breeds may appear here in several categories.

How Aggression Presents

Two things jumped out at me when first looking at this data. First, “Aggression” is not an individually measured trait. Dogs are carnivores and hunters - so it is unsurprising that many typical dog traits have an aggressive element. I would agree that “Sport Fighting” is the closest match to aggression as an area of concern, followed by perhaps “Police, Military, War” and then “Guarding, Protecting”. Saying that - Vermin Control, Sight Hunting and Scent Hunting also have potentially aggressive implications.

As in humans, aggression results from a complex interplay between genetics, environment, and individual experiences. The study’s findings should be viewed within this broader context.

Other studies break down aggression in ways such as - being aggressive to strangers, being aggressive to dogs, being aggressive when afraid, being aggressive when competing for food, being aggressive on a prey instinct, and being aggressive as a pain response. All of which could be present in any breed. This study can’t be used to predict aggressive behaviour because it isn’t designed to.

Second - pit bull isn’t one of the categories or breeds of dogs defined in the phylogeny. Neither is XL Bully - so the research cannot be used to support a ban on either breed.

The Anti-Dog Lobby Claims

“Dog brain study refutes every major claim of pitbull advocacy.”

That’s quite the claim in the headline of this article. Looking at the authors, I have some sympathy for them - I’m not going to demonise them as people because I think they have come to the wrong conclusions. The Author is Merrit Clifton, and his wife Beth Clifton has written here about their heartbreaking decision to euthanise their pit bull as they felt they could not control its aggression. It's also telling that they call a dichotomy between fighting dogs and ‘normal’ dogs. All the dogs in this study were normal dogs and pets. As far we know none of the dogs have ever even bitten someone.

Let’s start with the headline and sub-heading. To know if this is fair reporting, we first need to know the significant claims of pitbull advocacy and then see if the study refutes them. Here, we come up against a strawman logical fallacy. The author claims that pitbull advocates argue that there is no connection between form and function. This is a gross oversimplification.

The first thing to notice is that, despite the headline, as we saw when we looked at the study, “Aggression” is not one of the behaviours measured for, and “pit bulls” are not one of the reeds in the study. So it is hard to see how it can say much specifically about pit bull aggression. Yet, this article is using it to call not only for breed-specific legislation but the eradication of pit bulls! The article is also being used to support the UK ban on XL Bullies, one that we know is so poorly defined it will capture may cross breeds such as staffy-boxer or staffy-mastiff crosses - when the actual study excluded cross breeds!

The article says:

“Hecht et al in addition pointed the way toward recognising what specifically makes pit bulls by far the most dangerous breed category, even though only one acknowledged pit bull was part of their study.”

Merrit Clifton

So - they are not drawing their claims from the study. They are extrapolating to their existing conclusion. They are starting from a position that they believe pit bulls are more aggressive by breed, that the breed is deterministic to behaviour, and therefore that future studies will prove it.

“Hecht et al further established a basis for scientifically defining a pit bull, which can be refined through follow-up studies, by recognising physical traits that signal a propensity toward violence, as well as the capability for doing violence. This would bypass the difficulty of using DNA to identify pit bulls, much exploited by lawyers and lobbyists employed to fight breed-specific legislation.”

Merrit Clifton

The logic here is so circular it’s chasing its own tail. “We believe pit bulls are genetically violent but not genetically distinct, so we will identify dogs with some regions of the brain that we say make them violent, and then we will use that to classify dogs as pit bulls.”

The authors here want breed-specific legislation but also say that pit bulls are not a breed but might genetically have everything from Rottweiler to German Shepard in them.

The article goes on to highlight, with a quote from a DNA testing service owned by Mars Confectioners, that they can’t genetically test for ‘pit bull’ (which isn’t a recognised breed) because dogs that are visually identified as pit bulls are actually a mix of many different dogs.

“Due to the genetic diversity of this group, Wisdom Health cannot build a DNA profile to genetically identify every dog that may be visually classified as a pit bull. When these types of dogs are tested with Wisdom Panel, we routinely detect various quantities of the component purebred dogs including the American Staffordshire Terrier, Boston Terrier, Bull Terrier, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Mastiff, Bullmastiff, Boxer, Bulldog, and various other terriers and guard breeds. Additionally, there are often other breeds outside of the guard and terrier groups identified in the mix, depending on each dog’s individual ancestry,”

Wisdom Health

They are seeking to have their cake and eat it - they are saying, on the one hand, that there is a genetic, inheritable propensity to aggression while admitting that they can’t genetically identify a pitbull because they are not genetically distinct.

In the study the “Sport Fighting” dog analysis population was made of two Boston Terriers, one unrecorded breed, three boxers, and two bulldogs. Should all these dogs be banned?

These are the dogs in the study classified as “Sport Fighting.”

Yet, reading what Merrit Clifton says, he gives the impression that the study was of a statistically significant population of pitbull-type fighting dogs and that it was true.

“even (emphasis added) when the definition of a “fighting breed” is broadened to include, as they did, dog lines such as Boston terrier and boxer that have not been bred to fight in approximately 80 generations.”

Merrit Clifton

As you can see from above, these breeds were not diluting the sample pool; they comprised most of it.

The use of the sport-fighting as an analogy for aggression is understandable - but as I outlined above, if they are looking to identify dogs with aggressive tendencies who may attack people, shouldn’t war and police dogs also be banned?

That would add Dobermans to the list.

And if they want to eradicate unfortunate dog-on-dog attacks, where a dog might grab a smaller dog by the neck and shake it - they will also need terriers with a neurological propensity for ‘vermin-control ‘- So, among others, that means Dachshund, Schnauzers, and Yorkshire terriers.

And if there’s concern that dogs might attack people because their instinct is to guard people or property, then we can rope in Keeshond, Lhasa Apsos and Wheaton Terriers.

Another telling point is that this article is an outlier in its conclusions. Hecht et al. have had this study cited 74 times and covered in 162 news stories. A look at the news stories shows that none of them drew the same conclusions.

Sympathy for Trooper

I want to be clear, I don’t believe that the authors are bad people with sinister motivations; as far as I can tell, they want what I want - to reduce the severity and frequency of dog attacks and to improve dog welfare. I agree with many of their points - certain dog breeds are more likely to be abused and raised wrongly or abandoned. I disagree that BSL is the right approach because it doesn’t deal with the cause of the problem.

If problem owners create problem dogs, banning the breed doesn’t stop the bad owners from moving on to another genetic mix.

We know that direct experiences of dogs can dramatically change the individuals’ behaviours. Similarly, the authors experience with their pittie Trooper has led them to write off the whole breed of pit bulls, and by extension, any dog that gets a reputation. This is relevant because pit bulls have been banned in the UK since 1991, but dog attacks have increased. We are now expanding dog legislation in the UK to prohibit what will be deemed “XL Bullies” but which will encompass many cross breeds of Staffies, Boxers, Mastiffs and more.

Looking at Trooper’s history, I am not surprised that he was problematic because so much of what we know of his history and him as an individual raises red flags. Exploring the factors that may have influenced Trooper’s behaviour is crucial in understanding the complexity of dog aggression.

Let’s delve into each element and assess its potential impact on Trooper based on what we know from the article. In my article criticising Breed Specific Legislation, I shared nine environmental factors behaviourists say have a more significant role than breed on aggression. Let’s look at Trooper from those points of consideration.

Source of the Animal: Trooper was not acquired from a breeder, shelter, or pet store but was rescued very young due to a life-threatening situation. Dogs from unstable or unregulated sources may lack early socialisation and care, which can contribute to behavioural issues later in life.

Age at Rehoming: Trooper was rehomed at three weeks old, significantly earlier than the recommended age of 8-12 weeks. Early separation from the litter can lead to poor socialisation skills and difficulty adapting to new environments, potentially contributing to behavioural problems.

Reason for Acquisition: Trooper was acquired out of necessity to save his life rather than for companionship or work. While this is a noble reason, it may mean that the usual considerations for matching a dog’s temperament to the owner’s lifestyle and experience were impossible.

Owner Experience Level: Beth Clifton, Trooper’s owner, was a veterinary technician and former animal control officer, suggesting a high level of experience with animals. However, even experienced owners can face challenges with dogs having complex behavioural issues.

Socialisation Experiences: Trooper’s early removal from his litter meant he missed crucial socialisation experiences. This lack of early interaction with his mother and littermates could have hindered his social development, potentially leading to aggression.

Consistent Husbandry and Management Practices: The article suggests that Trooper received consistent care, including medical attention and a stable home environment. However, consistent husbandry alone may not rectify issues stemming from genetics or early life experiences.

Training: Trooper underwent training, including a nationally recognised puppy class, and his owner worked on his training for two years. Despite this, some of his behavioural issues persisted, indicating that factors beyond training were at play.

Sex Ratio of the Litter: The article does not provide specific details about the sex ratio of Trooper’s litter. The dynamics within a litter can influence a puppy’s early social experiences, but assessing its impact on Trooper isn’t easy without this information.

History of Aggression in the Pedigree: There is no mention of a known history of aggression in Trooper’s pedigree. While genetics can play a role in a dog’s predisposition to aggression, it’s important to distinguish between individual temperament and breed-specific traits.

One thing not covered here, is the Trooper was an amputee on pain medication, and that either the pain or the meds will likely have shifted his behaviour away from the mean.

While some of Trooper’s aggressive behaviour could be partially attributed to his genetics, it’s evident that a combination of early life experiences, lack of proper socialisation at a critical developmental stage, and possibly other unknown factors played significant roles. It’s crucial to approach dog behaviour, understanding that it is influenced by a complex interplay of genetics, environment, and experiences rather than attributing it to a single cause.

So what does this mean?

The MRI technique could be used to understand specifically better aggression in individual dogs within breeds - and how deterministic brain structure versus environment and history.

Commenting on the scientific research in the Colombian, Jeffrey Stevens, director of the Canine Cognition and Human Interaction Lab at the University of Nebraska, called the results exciting but cautioned

“The one thing that I think there’s a bit of disagreement on in the literature and in people’s views is how useful it is to map behaviors to breeds,... There’s often a lot of variation within a breed, across individuals.”

Jeffrey Stevens

One area of caution, and perhaps something for future research, is that while the dog breeds were classified into assumed careers, they were not doing anything related to that when MRI scanned - maybe a professionally trained scent hunter and a scent hunting breed dog would both have very different brains if they were MRId while hunting out a scent game!

And Hecht has indicated that future work will look to identify differences within breeds.

The study shows that dogs bred, perhaps generations ago, for sport fighting showed changes in the brain network that represent fear, stress, and anxiety responses, but any dog can bite when it feels fearful, stressed or anxious. Feeling fearful or anxious is not hotwired into pit bulls, XL Bullies, Staffies or boxers - otherwise, it would be evident in all of them all of the time. Instead, factors such as socialisation, training, environment and owner behaviours are all likely to have a more significant impact on an individual dog’s behaviour in a particular situation - so rather than the knee-jerk approach of BSL, a system that focussed on owner education and control would not only reduce more attacks but reduce the number of dogs who are fearful, stressed or anxious!

This is a fascinating study. As far as my knowledge goes, this is well designed, well carried out, well written and well received - but it cannot be used to justify the genocide of the breed-specific legislation - and, indeed, may instead be a foundational work that identifies the differences within breeds, and the similarities across breeds, which will give neurological support to the behaviourist belief that Breed-Neutral legislation is the correct way to reduce the severity and frequency of undesirable dog attacks.

Misuse of Science

Misinterpretations of scientific research can lead to oversimplified and potentially harmful conclusions, particularly in sensitive areas such as breed-specific legislation. Both the public and policymakers need to rely on a nuanced understanding of scientific studies recognising the limitations and specific contexts of the research.

While the study by Dr Hecht and colleagues is a groundbreaking contribution to canine neuroscience, its findings should be interpreted with caution and an understanding of the multifaceted nature of behaviour in dogs.

It's not true that those of us who are against this legislation say dog behaviours are nothing to do with nature and only to do with the environment. While we can strongly make the case that in many of the incidents we want to prevent, it is the “Bad Owner, not the Bad Dog”, this is an oversimplification of certainly my position and those of most of the anti-ban writers and campaigners I know.

There are, in general terms, some genetically influenced trends in behavioural differences between breeds. However, Breed-specific legislation is not a reasonable or practical solution, especially where the dogs caught up in it are so broadly visually defined.

Aggression, too, cannot be so simply defined - dogs are carnivores, and there are complex levels of aggression from stranger danger, resource guarding, hunting and reactions to fear pain or anxiety.

“Border collies are amazing at herding, but they aren’t born knowing how to herd. They have to be exposed to sheep; there is some training involved. Learning plays a crucial role, but there’s clearly something about herding that’s already in their brains when they are born. It’s not innate behavior, it’s a predisposition to learn that behavior”

Dr Hecht, Harvard Gazette

In simpler terms

“The truth is, it’s not nature or nurture. It’s the interaction between nature and nurture. It’s about the daily choices we make in handling and managing our dogs once we understand the instincts, capabilities, and limitations they bring to the table.”

Kim Brophey, Meet Your Dog

The UK must consider a legislative framework emphasising universal, non-breed-specific measures to create safer communities for humans and dogs.

If you agree, please do these three things for me:

Sign this petition to tell the UK Parliament.

Please email your MP with this form from bluecross.org

Please consider supporting the "Don't Ban Me Licence Me" campaign.

Thank you,

Rod

References

Hecht, E. (n.d.). About. The Canine Brains Project. Retrieved November 17, 2023, from https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/caninebrains/about

Hecht, E., Smaers, J., Dunn, W., Kent, M., Preuss, T., & Gutman, D. (2019). Significant Neuroanatomical Variation Among Domestic Dog Breeds. Journal of Neuroscience, 39(39), 7748-7761. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0303-19.2019

Harvard Gazette. (2019, September). Harvard researcher finds canine brains vary based on breed. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/09/harvard-researcher-finds-canine-brains-vary-based-on-breed/

Bittel, J. (2019, September 17). Dogs’ bodies, brains shaped by humans. The Columbian. Retrieved from https://www.columbian.com/news/2019/sep/17/dogs-bodies-brains-shaped-by-humans

Katz, B. (2019, September 3). Dog breeding has changed pooches’ brains. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/dog-breeding-has-changed-pooches-brains-180973038【13†source】.

Brophey, K. (2018). Meet your dog: The game-changing guide to understanding your dog’s behaviour. Chronicle Books.

Wendy Lyons Sunshine, MA. (2021, November). Is Your Dog Misbehaving—or Just Misunderstood? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/tender-paws/202111/is-your-dog-misbehaving-or-just-misunderstood

Sharon Begley. (2019, September 3). Canine MRIs Sniff Out How Human Preferences Shaped Dogs’ Hallmark Traits. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/canine-mris-sniff-out-how-human-preferences-shaped-dogs-hallmark-traits/

Carreira, L., & Ferreira, A. (2015). Anatomical variations in the pseudosylvian fissure morphology of brachy-, dolicho-, and mesaticephalic dogs. The Anatomical Record, 298(7), 1255-1260. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23171

Pilegaard, A. M., Berendt, M., Holst, P., Møller, A., & McEvoy, F. J. (2017). Effect of Skull Type on the Relative Size of Cerebral Cortex and Lateral Ventricles in Dogs. Frontiers in veterinary science, 4, 30. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2017.00030

Clifton, M. (2019, September 9). Dog brain study refutes every major claim of pit bull advocacy. Animals 24-7. Retrieved from https://www.animals24-7.org/2019/09/09/dog-brain-study-refutes-every-major-claim-of-pit-bull-advocacy/ on 16th November 2023

Clifton, B. (2018, May 15). Why pit bulls will break your heart. Animals 24-7. https://www.animals24-7.org/2018/05/15/why-pit-bulls-will-break-your-heart/

https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/caninebrains/doglifestudy

Addenda on Skull Shape Research

In “Phrenology of Dogs”, I discussed that skull shape and size alone is not a simplistic and determinative factor in brain morphology and, by extension, the neurological tendency to aggression. The Harvard study did reference a 2015 study into canine skull morphology and its impact: “Anatomical variations in the pseudosylvian fissure morphology of brachy-, dolicho-, and mesaticephalic dogs” But that study primarily focuses on the anatomical variations of the pseudosylvian fissure in different dog skull types. It does not address dog aggression, identification, or propensity in different breeds. The findings are more relevant to understanding canine brain anatomy and the implications for brain surgery and neurological studies in dogs.

It also looks at a 2017 study - t Effect of Skull Type on the Relative Size of Cerebral Cortex and Lateral Ventricles in Dogs. These research findings indicate a correlation between the cranial index (CrI) and cortical-to-ventricular volume ratio in dog breeds. They suggest that skull shape significantly affects the relative volume estimates of the cerebral cortex and ventricles in dogs. However, it does not establish a link between these anatomical variations and behavioural traits such as aggression or any behavioural characteristics.