Crassus Reborn: Disaster Capitalism

Crassus, the wealthiest Roman, bought burning buildings at bargain prices- only then having his slaves extinguish the flames. Now, as US slave labour tackles LA's Climate Wildfires, we ask - Cui Bono?

Wildfires are roaring across the Californian landscape consuming homes, habitats and humanity. The immediate narrative is devastation and loss. Yet behind the visible destruction of this climate crime is a question: One that must always be asked to understand late-stage-capitalism.

Qui Bono? Who Benefits? Who stands to profit?

Crassus: The Archetype Disaster Capitalist

"observing how natural and familiar at Rome were such fatalities as the conflagration and collapse of buildings, owing to their being too massive and close together, he proceeded to buy slaves who were architects and builders. Then, when he had over five hundred of these, he would buy houses that were afire, and houses which adjoined those that were afire, and these their owners would let go at a trifling price owing to their fear and uncertainty. In this way the largest part of Rome came into his possession"

- Plutarch's Lives, Crassus.

Marcus Licinius Crassus was the wealthiest man in late republican Rome. He made his fortune by exploiting crises. His private fire brigade refused to extinguish fires unless property owners sold to him at a pittance. Once the deal was secured, his slaves doused the flames, and Crassus rebuilt and rented out the properties at a substantial profit.

Crassus's methods were strategic and ruthless. He targeted insulae—Rome's densely packed apartment blocks—prone to fire due to poor construction and overcrowding. By purchasing these properties at rock-bottom prices during crises, he built a real estate empire that enriched him and built political influence.

Now, as Los Angeles burns, wealthy investors and corporations circle like vultures, seizing properties at fractions of their former value. Homeowners devastated by wildfires find themselves cornered, unable to rebuild, and pressured to sell. The Crassus model lives on, albeit in a modern guise and in more ways than just bargain hunting. Just as in late Republican Rome, slaves were putting out the fires.

Prison Labour: Modern-Day Exploitation

California's wildfires are being fought by incarcerated individuals earning as little as $1 per hour. Prisoners are coerced to risk their lives for wages that barely afford them a phone call in the name of rehabilitation. Their labour saves the state millions annually: professional firefighters receive an average annual salary of $74,000 plus benefits. Using prison labour, California saves an estimated $80-100 million annually.

And this isn't some new Trumpian development—California has relied on incarcerated firefighters since 1915. California's Department of Corrections says that the work is voluntary and paid. However, California requires prisoners to work. Not working is not an option.

XIII - Unlucky for some

"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Thirteenth Amendment, US Constitution.

The roots of this exploitation lie in the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which abolished slavery "except as punishment for crime." This loophole paved the way for convict leasing and chain gangs post-Civil War practices that disproportionately targeted African Americans.

Today, the use of prison labour perpetuates systemic inequality.

Not only are the prison firefighters working for lower pay - they are at higher risk of death and injury. Compared to professional firefighters, they are four times as likely to be injured and eight times as likely to suffer from smoke inhalation.

Prisoners are told they are learning a skilled trade; however, few can become firefighters upon leaving prison. Most Californian fire departments require their Firefighters to have Emergency Medical Technician licenses. Yet, in California, felons cannot hold an EMT license until they have been out of prison for 10 years. However - incredibly - these departments allow the released prisoners to work as firefighters - as long as they are unpaid volunteers.

By all means, it can be a good opportunity, but maybe that just highlights how bad conditions in prison are—some inmate firefighters are saying that it's dangerous and they are underpaid, but for the first time, they are feeling recognised, people are appreciating them, and they are spoken to like humans.

The Machinery of Disaster Capitalism

"The widespread abuse of prisoners is a virtually foolproof indication that politicians are trying to impose a system--whether political, religious or economic--that is rejected by large numbers of the people they are ruling. Just as ecologists define ecosystems by the presence of certain "indicator species" of plants and birds, torture is an indicator species of a regime that is engaged in a deeply anti-democratic project, even if that regime happens to have come to power through elections."

Naomi Klein - The Shock Doctrine

Naomi Klein's concept of disaster capitalism describes how crises are exploited to push through neoliberal economic policies and profit-driven agendas. In LA, the wildfire crisis has created opportunities for deregulation, privatisation, and the consolidation of wealth. Insurance companies, real estate developers, prisons for profit, and even disaster relief contractors are beneficiaries of this systemic inequity.

The mechanisms of disaster capitalism begin with "shock therapy." The disorientation caused by crises is leveraged to implement drastic changes with little or no oversight. In the case of LA's wildfires, especially under the second Trump administration, we can expect to see scrapping of environmental regulations to facilitate 'reconstruction' and prioritising commercial interests and planning permission over ecological or community needs.

We can confidently say this because it happened in Santa Rosa and Paradise.

Think Twice: Another Day for you and me in Paradise.

The Tubbs Fire was one of the most devastating wildfires in California history. It tore through Santa Rosa in October 2017, destroying over 5,600 structures and claiming at least 22 lives. Entire neighbourhoods, such as Coffey Park and Fountaingrove, were reduced to ashes. Thousands of residents were displaced. In the wake of this destruction, the rebuilding process revealed and increased deep inequities and speculative buying that would make Crassus blush.

Before residents could even face the trauma of losing their homes, real estate investors began targeting the devastated areas. Property values in Santa Rosa dropped significantly in the fire's immediate aftermath, making it an attractive opportunity for speculative buyers who sought to profit from the crisis. Reports emerged of developers pressuring distressed homeowners to sell quickly - purchasing fire-damaged lots at reduced prices, often before insurance claims were fully processed. Many long-term residents, unable to afford the rising rebuilding costs, were effectively pushed out of their communities.

Meanwhile, construction and rebuilding costs soared due to labour shortages, supply chain issues, and heightened demand. These factors disproportionately affected lower-income residents who lacked the financial resources to cover out-of-pocket expenses not covered by insurance. As a result, much of the emerging housing catered to higher-income buyers, exacerbating the area's affordability crisis.

The state implemented measures to expedite rebuilding, greasing permits, and offering financial incentives. These efforts disproportionately benefited wealthier developers and homeowners. Affordable housing initiatives struggled to gain traction, displacing many renters and low-income residents. Even years after the fire, Santa Rosa's population has struggled to reach even half its pre-disaster levels. The Camp Fire of November 2018 obliterated the town of Paradise, destroying over 18,000 structures and claiming 85 lives. It was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California's history to that date.

They Paved Paradise

Everything had changed. Every property within the Town of Paradise was impacted by the fire. Burnt trees and piles of rubble now stood where a green envelope had once drawn the community together. Paradise had been in the direct line of fire of the Camp Fire, at the time the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California’s history.

FEMA Case Study

For most residents of Paradise, the dream of returning has remained out of reach. The cost of rebuilding homes has often grossly exceeded insurance payouts. Renters faced even greater challenges. With a lack of affordable housing options, many former residents have been forced to relocate permanently to nearby cities or other states. Eight years later, the population is only around a third of pre-fire levels. Only around 600 new houses a year are being rebuilt.

Federal aid and state programs, while helpful, were insufficient. Complex application processes and delays in disbursements meant that some individuals abandoned plans to rebuild altogether, leaving a significant portion of the town's original population excluded from the recovery process.

Gentrification by Disaster

"Resilience gentrification is the process in which only the wealthy can pay the increased costs of building climate-resistant structures, resulting in displacing poorer people"

Gould and Lewis 2021

Higher-income residents and developers have taken advantage of opportunities to build larger, more luxurious homes on the cleared lots. This has led to concerns about "gentrification by disaster," where the rebuilt areas cater to a wealthier demographic while pushing out its original working-class population. Some approved developments feature sprawling estates with state-of-the-art fireproofing measures, making them inaccessible to many of the town's former residents. The inequality is embedded in three phases.

Phase 1: Climate Demolition

The disaster wreaks havoc, destroying homes, infrastructure, and critical services like schools, hospitals, and water systems. This devastation forces communities to flee, sometimes permanently. While this phase offers a chance to rethink how rebuilding can support environmental recovery or promote sustainability, the urgency to act often favours resilience-focused rebuilding over leaving nature to heal.

Phase 2: Recovery Policy and Planning

Governments step in to shape recovery, often with well-intentioned changes to make communities more disaster-resilient. Building codes may be updated to mandate higher elevations for flood-prone areas or to incorporate more robust materials and infrastructure. These changes, while critical for future resilience, come at a cost. Because displaced residents are scattered and often unable to engage with the process, they have little say in shaping these plans.

Phase 3: Resilience Gentrification

As new, more disaster-resilient homes and infrastructure are built, their higher costs make them unaffordable for many of the original residents. Property taxes rise in tandem, pricing out those who can't afford the upgrades. This leaves room for what Gould and Lewis call the "sustainability class"—a wealthier demographic that can afford to live in these revitalised, climate-resilient areas.

Disaster recovery, even well-intentioned disaster recovery, deepens existing inequalities when rebuilding efforts fail to prioritise equity. When disaster recovery is being done for profit, it's accelerated and exacerbated. In both Santa Rosa and Paradise, speculative buying and rising costs displaced long-term residents, while wealthier individuals and developers capitalised on opportunities created by tragedy. No. Don't call these tragedies but crimes.

Policies focusing on affordable housing, strict regulations on speculative practices, and equitable access to recovery funds would help. Without these measures, wildfires and other climate disasters—hurricanes and floods—will continue to favour the privileged at the expense of vulnerable communities.

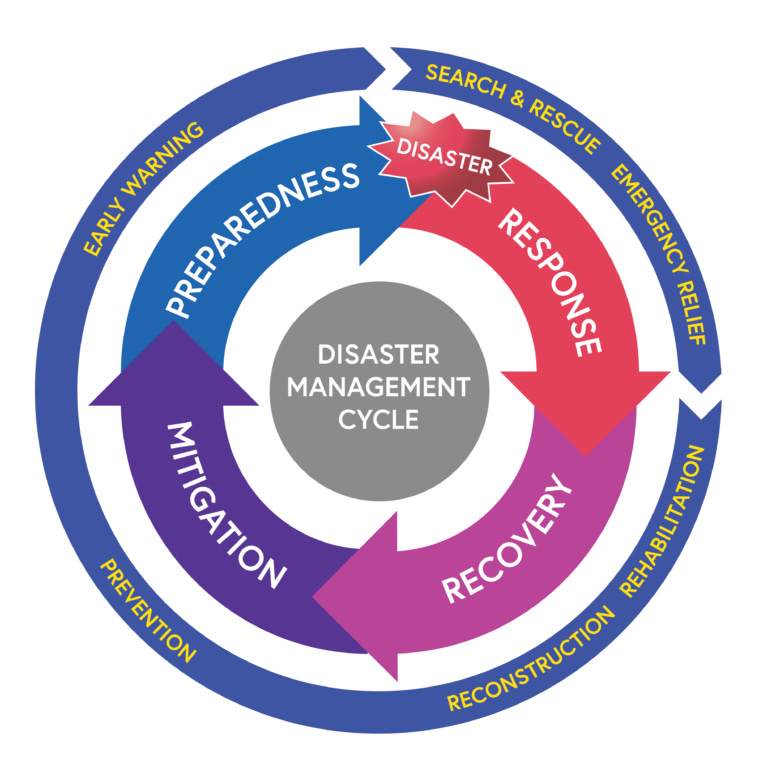

"This diagram illustrates the disaster management cycle. Once the disaster occurs, the community responds immediately. When the initial disaster subsides, disaster recovery starts, but it often takes years for a community to recover. Ideally, communities learn from the disaster, mitigating any future problems and beginning to prepare for the next disaster." https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/socproblems1e/chapter/oo14-4/

The Insurance Companies Cashed Out

The Camp Fire was the most expensive natural disaster in history in terms of insurance payouts. Even then, Many people found that the insurance payout didn't cover the cost of cleanup and rebuilding. But the insurance companies took note and read the writing on the wall that these climate crimes would become more frequent.

They took their profit and cashed out of the game, cancelling tens of thousands of insurance policies in the run-up to the latest fires. In California, State Farm announced last year that it would be terminating coverage for 72,000 residential properties within the state, including both houses and apartments. Since 2019, over 100,000 residents of California have experienced a loss of their insurance coverage, as indicated by an analysis of insurance data conducted by the San Francisco Chronicle.

Citizens have been abandoned, in the path of preventable fires caused by avoidable climate change, done for profit. There is a government-backed insurance plan, but it costs over $3,200 a year, more than double California's average home insurance rate. Analysis shows this impact on the housing market - people are moving away from areas where they can't get insurance, driving property prices down. However, California is looking at regulations that will facilitate coverage in the future by allowing insurance companies to pass on the cost of re-insuring to policyholders.

The upshot is that there will be a temporary depression of property value that Crassus-type speculators can step into and weather the downturn until the property regains its value when it becomes insurable—but with the additional costs borne by the consumer.

Toxic Investment

For all that, it could still be a literally toxic investment. When wildfires burn through these Californian neighbourhoods, they leave a poisonous nightmare in their wake - melted lead, exposed asbestos, toxic ash and popping off ammunition may mean people can't return for many months - especially with an unprecedented disaster on this scale. When the state is involved, landowners may qualify for free cleanup - but clearing one lot might take 15 loads of trucks and teams in hazmat suits' burrito wrapping' toxic waste to go to landfill sites that have not yet been identified.

Those who can afford it might pay for private cleanup. Those who can't can wait, or sell cheap to a Crassus corporation who can sit and wait for it to be cleared and pull in a profit later. And when corporations buy the land - will they do the most effective job clearing it up? Or just the most cost-effective? If they do it at all?

The cleanup from the Camp Fire became the largest hazardous materials cleanup in California's history. With almost 30,000 people in the town and about 3,000 in the nearby rural areas, it took a long time to clean up. Because it was difficult to find temporary housing for everyone, residents were allowed to stay on their burned-out properties, exposing them to harmful materials. The winter rains began, and hazardous contaminants seeped into the ground and contaminated nearby waterways. There was also worry about benzene contamination coming from melted plastic pipes. Initially, Paradise tested parts of its water supply and found that 22 out of 24 water systems passed tests. However, later on, the Paradise Irrigation District reported that the water was contaminated and unsafe to drink.

The cleanup required after these 2025 fires is an order of magnitude bigger. It's not clear where the toxic waste will go—even for the earlier fires, sites in California could not be found, and waste ended up being shipped into Nevada for burial.

Disaster Profiteering Incentivises Disasters

Crassus's legacy should be a cautionary tale, not a business model. Disaster profiteering isn't just unethical —it incentivises maximising future disasters. Just like for profit prisons and cheap prison labour incentivise incarceration.

Indeed, slightly falling prison populations in California were highlighted in 2024 as a wildfire safety issue!

At the moment, we have companies profiting from creating Climate Change. While people are losing everything from the climate crime fires, the government is renting out slave labour, all so speculative companies can profit from the recovery.

This is not sustainable.

This is not humane.

While the politically powerful Crassus profited from Rome's daily fires, there was little chance of firefighting being developed as a public service for the benefit of all.

After Crassus, the aedile Egnatius Rufus made 600 slaves available, at no cost, to fight fires—and won popularity with the people for this public service. His reward? A jealous Augustus, most likely wary of his potential as a popular rival, had him found guilty of conspiring against the principate and executed—then promptly set up Rome's first truly professional and publicly funded firefighting force of 3,500 free men—the Vigiles Urbani.

The Fate of Crassus

And the ultimate fate of Crassus? Death by Hubris. In search of greater glory and personal fortune, at the age of 63 he over-confidently made an ill-fated invasion in the Middle East, crossing the Euphrates to 'conquer the Parthians'. He was deceived, deserted and decapitated: The story later told that his head was first used as a prop in a production of Euripides, then had molten gold poured down his throat, mocking his insatiable desire for wealth.

Well, as they say in Virginia - sic semper tyrannis

Note - This is a huge subject, of an ongoing disaster, in a collapsing empire - there is much more that could be said on for-profit prisons and the use of prisoners as cheap labour - not just sewing mailbags and punching licence plates, but hired out to work in KFC, Burger King and hundreds of other places of employment. I've not scratched the surface of Fire Service funding cuts, or the increase in LAPD funding - and the police acting as protectors of capital in time of disaster, not as serving the public of the War on the Homeless and how they will be impacted, on the Private ownership of much of California's water, diverted to support Cashew nut monopoly billionaires. Or how, with so much wealth and power in one man, Crassus's death destabilised the Late Roman Republic - collapsing the first triumvirate. Within a short period, Ceaser and Pompey plunged into thirty years of Civil War and destabilisation that saw the Republic fall and autocracy take its place.

References

Democracy Now. (2018, August 9). $1 an hour to fight largest fire in CA history: Are prison firefighting programs slave labor? Retrieved from https://www.democracynow.org/2018/8/9/1_an_hour_to_fight_largest

Governing. (n.d.). What happens when there aren't enough California inmates to fight wildfire? Retrieved from https://www.governing.com/workforce/what-happens-when-there-arent-enough-california-inmates-to-fight-wildfire

Khamenei.ir. (n.d.). Modern slavery: How the world's largest prison population developed. Retrieved from https://english.khamenei.ir/news/3622/Modern-Slavery-How-world-s-largest-prison-population-developed

Crassus, For-Profit Fire-Chief or Speculative Property Developer? – Liv Mariah Yarrow. https://livyarrow.org/2020/04/21/crassus-for-profit-fire-chief-or-speculative-property-developer/

Klein, N. (2007). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Los Angeles Times. (n.d.). Wildfire property speculation. Retrieved from

https://www.latimes.com

National Geographic. (n.d.). Crassus: Rome's richest man. Retrieved from

https://www.nationalgeographic.com

New York Post. (2023, December 15). Alabama inmates forced to work at Burger King, McDonald's for next to nothing: Suit. Retrieved from https://nypost.com/2023/12/15/news/alabama-inmates-forced-to-work-at-burger-king-mcdonalds-for-next-to-nothing-suit/

New York Times. (n.d.). Hurricane Maria and privatisation. Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com

Plutarch. (1916). The parallel lives. (Vol. III of the Loeb Classical Library edition). Retrieved from https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Crassus*.html

The Atlantic. (n.d.). Hurricane Katrina and gentrification. Retrieved from

https://www.theatlantic.com

The Guardian. (n.d.). Incarcerated firefighters. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/08/la-wildfires-incarcerated-firefighters

Time. (n.d.). Inmate firefighters: Injuries and death. Retrieved from https://time.com/5457637/inmate-firefighters-injuries-death/

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (n.d.). Paradise, California: Rebuilding resilient homes after the Camp Fire. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/case-study/paradise-california-rebuilding-resilient-homes-after-camp-fire

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Camp Fire (2018). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_Fire_(2018)