There's a passage in Ernest Hemingway's novel The Sun Also Rises in which Bill asks Mike how he went bankrupt. "Two ways," Mike says. "Gradually, then suddenly." We die the same way.

We are dying slowly every day, and then all at once, it comes upon us. I should know; I've died twice and lived to tell the tale.

I was lucky enough to 'die' when I was eleven but too foolish to make good use of it. I was involved in an incident and was injured to the extent the paramedics told the police that I would not survive to the hospital, so the police filed a fatal accident report.

So it goes.

As it was, a triage decision by a paramedic saved me. I was taken to a bigger hospital further away than the one the ambulance had come from, to Belfast rather than Antrim. One with world-class reconstructive and neuro-surgeons honed on the semi-warzone that was the troubles in the late 80s and early 90s. They still say Belfast is one of the leading centres in the world for knee surgery. It was touch and go, with a long time in a coma and a slow recovery.

If I'd been exposed to Philosophy as a child, maybe I would have taken a wise lesson from it and made better use of the experience instead of another decade or more of misspent risk-taking and treating life cheaply.

The second time I 'died' was, thankfully, also only in the bureaucratic sense, but this time with somewhat less trauma.

“Through accidental happenstance… I was presumed and declared legally dead in the State of California.”

Through accidental happenstance more than careful financial planning, I had become a foreign shareholder in an American Corporation. Then thanks to a mix of executive dysfunction, misunderstanding of arcane unfamiliar American regulatory requirements, and several rather more pressing local distractions, somehow, some critical paperwork fell through the cracks with the US broker and, in my absence and silence, I was presumed and declared legally dead in the State of California.

“He's spending a year dead for tax reasons”

-Ford Prefect, on Hotblack Desiato The Hitch-hikers Guide to the Galaxy

I have to say the Californian State employees themselves were most understanding on the phone, yet strangely unwilling to take my word for it that I was very much alive, kicking and wanting my dollars back from Uncle Sam.

After some negotiation, the matter was resolved with a visit to an approved Notary: a small woman in a tiny office in an old shipping firm building, up an ornate staircase still branded with themed Victorian tiles. For a small fee, she embossed an American compliant piece of paper and, once more, I was alive in California, albeit with no legal right to actually live there.

I knew what a Memento Mori was this time and could take the hint. The mild inconvenience of being technically dead in a foreign land led me to rethink some things.

Let each thing you would do, say, or intend be like that of a dying person."

—Marcus Aurelius.

Cruelest Day

Then, in August 2017, I lost both my Mother and my dog, Boston, within hours of each other. My Mother had been in palliative care after a series of strokes, and I was over in Northern Ireland, where the family gathered in the hospital for the final weeks before the inevitable. She passed on a Sunday Morning, and it was back in my childhood home a few short hours later when I got the news about our dog Boston; he had been a little ill before I had left Scotland some weeks previously but had then taken a sudden turn for the worse, and needed to be euthanised unexpectedly.

I’d been composed and prepared at the hospital, but Boston’s death was a blow: not only was it unexpected, but it just seemed so needlessly cruel.

"Unfamiliarity lends weight to misfortune, and there was never a man whose grief was not heightened by surprise."

– Seneca

In retrospect, of course, I should have been expecting it. Death is the only promise that is always kept.

Memento Mori

"At the times when you are delighted with a thing, place before yourself the contrary appearances. What harm is it while you are kissing your child to say with a lisping voice, "To-morrow you will die"; and to a friend also, "To-morrow you will go away or I shall, and never shall we see one another again"?"

– Epictetus

In our library, I have shared my Phrenology Head. In my office, however, I have a different curiosity - a Human Skull*, a souvenir of a foreign trip, sits behind me. He is my Memento Mori. I pass him to get to and from my desk several times a day. He constantly looks over my shoulder on video calls as a reminder to myself and others of our shared mortality.

The Stoic Practice of Memento Mori translates as "'Remember to die" and figuratively translates to Remember you will die. The practice is to consciously focus some time regularly to address and accept the fact that you and everyone you know will die.

By addressing this taboo and reminding ourselves, it helps us to make better use of life. Theoretically, it should help us reduce procrastination - and also remove the shock and lessen the grief a little when there is a death.

It's not to eradicate grief; the Stoics are not emotionless, and eliminating emotion like this is neither practical nor desirable, but rather to rationally prevent grief from becoming crippling by seeing it in perspective. Death is in line with nature and so cannot be evil.

More Sage than Wretch

“Call no man happy until he is dead.”

- Solon

Solon, a wise Athenian statesman, legislator, and poet, and one of the seven sages of Greece, is often credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. According to one apocryphal story, Solon visited the wealthy king Croesus in Lydia. Croesus, known for his immense wealth, asked Solon who the happiest man in the world was, expecting Solon to flatter him by choosing him.

However, Solon, known for his wisdom and perspective on life, named other individuals as examples of happy lives. He pointed out that a happy life was not just about wealth or power but about living a good life and having a good death. Solon emphasised that life could only be judged in its entirety at its end, as fortune could change at any moment. He famously said, "Call no man happy until he is dead," signifying that a life's actual value can only be assessed when it's complete and unchangeable by future misfortunes. Croesus mocked him at the time - then, after his fall from grace when about to die, realised the truth in the statement, and he wept “Solon!, Solon!, Solon!”

Time to say goodbye

"If the room is smoky, if only moderately, I will stay; if there is too much smoke I will go. Remember this, keep a firm hold on it: the door is always open."

Epictetus

We lost my best pal, Barney, recently. This time, unlike with Boston, I was present, and it was not at all unexpected. Barney lost a battle with Lymphoma - and he was in Palliative care - we knew the chemotherapy we had tried had not worked and that it would be unfair to put him through more - that he would need to be put to sleep soon. So there was a short melancholy window when we knew there was no hope, but he was still essentially himself, with the same personality, some playfulness and passion for stones.

When Epictetus talks of the smokey room, he is telling us that suicide is always an option if things get too bad - but this is not to be interpreted in an overly negative way. The message is that things can't be that bad if it's worth sticking around. And so if things are bearable, it's best to choose to bear it without complaint. ( easier said than done) But if something truly is unbearable, then 'the door is always open'.

But deciding to open the door for a loved one in your care - That's a big responsibility. We have a duty to make the right decision at the right time. It's a covenant we make when we adopt our pets. A promise I'd been unable to keep with Boston, that we will make the hard decisions, not shirk from our duty to them, and be there and care for them right to the end.

Of course, we did not want to take it too soon when he was not in any pain - still enjoying food and walks. But also, we did not want to leave it too late, to have him suffer.

It is undoubtedly a very emotional decision, but having a duty to be logical and rational, I found a framework used by Vets. It didn't decide for us or even made the decision easier, but it helped reassure me that we were making the right decision at the right time.

The HHHHHMM Scale

The HHHHHMM Scale is a system that Vets use to assess quality of life, which could otherwise be subjective. Assessing quality of life involves considering various physical and emotional factors. The acronym stands for Hurt, Hunger, Hydration, Hygiene, Happiness, Mobility, and 'More Good Days Than Bad'.

Hurt: Assess the level of pain your dog is in and whether it's being managed effectively through medication.

Hunger: Monitor your dog's appetite and weight. Is your dog eating willingly and maintaining a healthy weight?

Hydration: Check for signs of dehydration, like dry gums or decreased urination.

Hygiene: Consider whether your dog can keep itself clean or needs assistance. Look for signs of skin breakdown or infections. An increase in 'accidents'.

Happiness: Evaluate your dog's emotional state. Is it interested in its surroundings, or has it become withdrawn? Does it still enjoy interaction and play?

Mobility: How well can your dog move around? Can it walk and engage in light exercise, or has its mobility significantly decreased?

More Good Days Than Bad: This is an overall assessment. Are the good days outnumbering the bad ones?

In veterinary practice, it can be used more as an algorithm, where each category is scored on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the best possible state. A total score of over 35 out of 70 generally suggests an acceptable quality of life.

I didn't use it quite so clinically, but just as a mental framework to gather my thoughts. We spoiled him rotten while he was with us and tried to give him a good life. As Solon knew, to give him a good life, we needed to give him the best death we could. It was time.

"To lose a friend is the greatest of all evils, but endeavor rather to rejoice that you possessed him than to mourn his loss."

– Seneca

They Shoot Horses, Don't they?

Thinking about the HHHHHMM scale as used for animals made me think of how I should consider and measure our own quality of life. How is it that, as a society, we can euthanise animals for 'humanitarian' reasons but then let humans in the same situation suffer?

The phrase "They shoot horses, don't they?" is the title of a 1935 novel, which depicts desperate characters participating in a gruelling dance marathon, to exhaustion, during the Great Depression. Often used to suggest that when a situation becomes hopelessly dire, a merciful end is sometimes the best solution. It originates from the practice of euthanizing injured horses, as they cannot recover well from severe injuries, symbolizing the idea of mercy in the face of relentless suffering.

Assisted dying, a topic at the heart of end-of-life care debates, presents a complex interplay of ethical, historical, and practical considerations. Once a benchmark, The Liverpool Care Pathway was criticised for its one-size-fits-all approach, often prolonging suffering rather than alleviating it (NHS England, 2013). Assisted dying, by contrast, offers a more individualised and compassionate end-of-life option.

The current mess of legislation highlights the hypocrisy of 'Do Not Resuscitate' (DNR) orders. While DNRs are passively accepted, allowing preventable, even painful deaths to occur naturally, the active choice of painless, composed, assisted dying remains controversial despite both being decisions about the end of life.

Bake-off's Prue Leith is currently campaigning for the right to assisted dying after watching her brother die in agony. She described how her brother, David, suffered immensely, with morphine providing inadequate pain relief.

The morphine gave pain relief for three hours, but he was only allowed morphine every four hours because it is addictive - even though he was in palliative care. This meant in his final weeks, he was needlessly in extreme pain for six hours a day.

"When David was full of morphine, he was delightful. He would be chatting to his family and telling them he loved them, and he was quite happy to die because he had a great life They are the sort of memories they should have been left with.”

Prue Leith

Leith argues that those who are terminally ill should have the right to die on their own terms - that they are not suicidal, they don't 'want to die' - but they have no choice but to die and should have the power to choose a good death.

The Hierarchy of Needs

"Man is a perpetually wanting animal." -

Abraham Maslow

Some cases, such as her poor Brothers, seem self-evident and merciful. But how can we assess someone's quality of life? What was evident to me straight away is that you cannot simply apply the HHHHMM scale to humans. It is, essentially, only physiological. By that measure, where would Helen Keller sit - or Christy Brown? Yet they clearly had good quality of life, with meaning and purpose.

The psychologist Abraham Maslow introduced a theory in his 1943 paper "A Theory of Human Motivation" that has since become a cornerstone in understanding human psychology. This theory, "Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs", posits that human beings are motivated by a hierarchy of needs. It's like climbing a ladder, where each rung represents a different set of needs, and one must satisfy lower-level needs before moving to higher ones.

The first level, at the base of the pyramid, is Physiological Needs: the essentials for survival – food, water, warmth, rest. Imagine a baby crying for milk; that's the most primal need expressing itself. Next, we climb to Safety Needs: security and safety. This is physical safety, employment, resources, and health. Think of a young adult striving for a stable job and a safe neighbourhood, laying the groundwork for a secure future. The third level is Belongingness and Love Needs: intimate relationships and friends. It's the warmth of family gatherings, the camaraderie among friends, and the comforting embrace of a loved one. We are social creatures, after all. Ascending further, we reach Esteem Needs: prestige and the feeling of accomplishment. It's the pride in receiving an award, the satisfaction from a job well done, and the status of being recognised in your community. Initially, at the peak was Self-Actualisation: achieving one's full potential, including creative activities. It's the artist losing herself in her painting, the scientist making a groundbreaking discovery, and the moment when one feels genuinely fulfilled. But Maslow later added a new final stage - Self-Transcendence: a need to go beyond the self and help others achieve their potential, found in acts of altruism and spirituality.

Like a map of human motivation, this hierarchy guides us through life's journey. Yet, as Maslow noted, life is not a rigid climb; we often fluctuate between these needs, and the journey is uniquely personal.

Would it be valid to use the hierarchy of needs and score against each level out of 10 to determine quality of life? That would give us pointers to grow or at least a framework to assess it.

Analysing Maslow's Hierarchy Through the Lens of Stoicism

For a Stoic, there are immediate problems with considering the hierarchy of needs in this way. Stoicism is virtue-based ethics, where the quality of life is based on eudaimonia. A well-flowing life.

For Stoics, achieving eudaimonia means leading a life aligned with one's rational nature and so per virtue, leading to true fulfilment and happiness.

Stoicism teaches the importance of virtue and understanding the dichotomy of control, distinguishing between what is in our power (our own actions and responses) and what is not (external events and the actions of others). It's less about external circumstances and more about one's internal state and moral character.

By Stoic definition, external circumstances not in our control may, if they don't impede virtue, be pleasant to have so be "Preferred", but they cannot be required to have a good life, so we should be indifferent to it.

If it is beyond our control but impedes virtue, it should be un-preferred and certainly could not count towards a quality of life.

But using these Stoic concepts, we can analyse Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs to understand how each level aligns with the Stoic principles of the dichotomy of control and pursuit of virtue.

Physiological Needs (Food, Water, Rest, Movement etc.):

The dichotomy of Control: These are partially within our control. We can decide our response to hunger or tiredness, but we cannot control the availability of resources. We can choose to try and exercise our bodies, but we could be involved in an incident that kills us or puts us in a coma.

Virtue and Indifference: Meeting basic needs is a 'preferred indifferent' in Stoicism. It's preferred because it supports physical well-being but indifferent because it does not inherently contribute to virtue. This can be a complex concept when first introduced to Stoicism, and it's undoubtedly easier for Sages than Wretches - but fundamentally, while it is desirable to eat to avoid hunger pains, not having food to eat does not harm your character; even if you starve to death.

Safety Needs (Security, Employment, Health):

The dichotomy of Control: These elements are mainly outside our control. We can strive for them, but external factors often play a significant role - so they should not be considered required for quality of life.

Virtue and Indifference: Safety is a preferred indifferent. It's conducive to a stable life, which can aid in pursuing virtue, but its absence does not prevent one from being virtuous.

Belongingness and Love Needs (Intimate Relationships, Friends):

The dichotomy of Control: Relationships are outside our complete control as they involve others' actions and feelings, BUT we have a duty to think as Cosmopolitans and to be good friend.

Virtue and Indifference: Healthy relationships are preferred indifferents. They can provide emotional support and opportunities for practising virtue-supporting practices like kindness and empathy, but they are not technically essential for a virtuous life.

Esteem Needs (Prestige, Feeling of Accomplishment):

Dichotomy of Control: Esteem, especially when it depends on others' opinions, is absolutely outside our control. As a need, this should be eradicated from the list. It is a message of ego, and ego is the enemy. Besides

"If you want to improve, be content to be thought foolish and stupid with regard to external things.”

Epictetus

Virtue and Indifference: Esteem is an 'un-preferred indifferent' in Stoicism. Seeking external validation can lead away from virtue by prioritising others' opinions over right action.

Self-Actualisation (Achieving Full Potential, Creative Activities):

The dichotomy of Control: Self-actualisation is within our control as it depends on personal growth and choices. If you are not self-actualising, you are not living a good life.

Virtue and Indifference: This aligns closely with Stoicism's concept of living according to nature. It's a preferred indifferent if it leads to the development of personal virtues.

Self-Transcendence (Helping Others, Altruism):

The dichotomy of Control: Our actions towards others are in our control (but their impact is not.)

Virtue and Indifference: This is a preferred indifferent. Stoicism values social roles and community. Helping others can be an expression of virtue, but the focus should remain on the intent rather than the outcome.

So, while Stoicism recognises the importance of the basic physiological needs and the duty to social relationships as preferred indifferents that can support a virtuous life, it emphasises that true virtue can only lie in things within our control – our actions, responses, and character. External achievements and validations (esteem, prestige) are seen as un-preferred, or at best neutral, indifferents. The ultimate goal is to live following virtue, the only true good in Stoic philosophy, which also means dying in accordance with virtue.

Quality of life requires quality of death.

In the modern context, the reality of ageing and disease, especially with the rise of conditions like Alzheimer's (Alzheimer's Society, 2021), brings into focus the need to discuss the quality of life in our later years. If we pride ourselves on being rational and moral beings, then we should have the autonomy to decide our fate, particularly in the face of incurable illness and suffering.

The Dignitas argument, presented by Dignity in Dying (2021), highlights the plight of individuals forced to travel abroad to access assisted dying, adding to their and their families' suffering.

The human element in this debate is poignantly illustrated through personal stories like Prue and her brother. These narratives often reveal the unnecessary suffering and the agonising choices faced by those at the end of life. The current legal framework places healthcare professionals in a challenging position, often unable to provide what they may deem the most compassionate care due to legal constraints.

Addressing counterarguments is crucial. The slippery slope argument suggests that legalising assisted dying could lead to increased deaths. However, evidence from places like Oregon, where assisted dying is legal, shows that strict regulations and safeguards are effective (Oregon Health Authority, 2020).

While the sanctity of life is undeniably important, if we can't say we have had a good life until we have had a good death, then quality of death is needed for quality of life. Individual autonomy in making end-of-life decisions is equally vital.

Delving deeper into ethical considerations, we encounter the dilemma of end-of-life choices. The principle of autonomy in healthcare, advocating for the right to make decisions about one's own body and life, often clashes with societal norms and legal frameworks. Palliative care, while aiming to provide comfort, may not suffice in alleviating suffering for some, making assisted dying a preferred alternative. Healthcare providers face a moral quandary in balancing their duty to preserve life, respecting patient autonomy, and alleviating suffering.

From a historical and philosophical perspective, Stoicism's advocacy for the right to die in the face of truly unbearable suffering provides a foundation for modern arguments in favour of assisted dying. The evolving societal attitudes towards death and autonomy reflect a growing acceptance of individuals having more control over their end-of-life decisions.

Examining legislation in countries where assisted dying is legal, such as Canada and the Netherlands, offers insights into structuring laws that ensure safety, dignity, and autonomy (Government of Canada, 2020; Dutch Government, 2021). The legalisation of assisted dying impacts not just individuals but also their families and society, potentially alleviating the emotional and financial burdens of prolonged end-of-life care.

But integrating assisted dying into the healthcare system requires ethical guidelines, training for healthcare providers, and support systems for patients and families, ensuring a compassionate approach to this deeply personal and complex issue, and if there was ever a place for practical philosophy, it is here.

We can't all be Cato.

When Cato the Younger committed suicide, it was in emulation of Socrates, and as a political martyr to the old Republic, to not face the shame of being pardoned by Julius Caesar. When Seneca did it a century later, it was in the context that if he had been executed, his family would have forfeited their property and status.

These are very different circumstances to the modern world.

Now, the ethical, historical, and practical considerations surrounding assisted dying present a compelling case for its legalisation but under strict regulations. It is a matter of balancing individual autonomy with societal and ethical norms and ensuring that those facing the end of their lives can do so with dignity and minimal suffering.

I would advocate that in certain limited circumstances, assisted dying emerges not only as a desirable choice but as a compassionate alternative to prolonged suffering. The development of something like Maslow's hierarchy of needs, but in a philosophical framework, considering quality of life could be part of that conversation but needs more work.

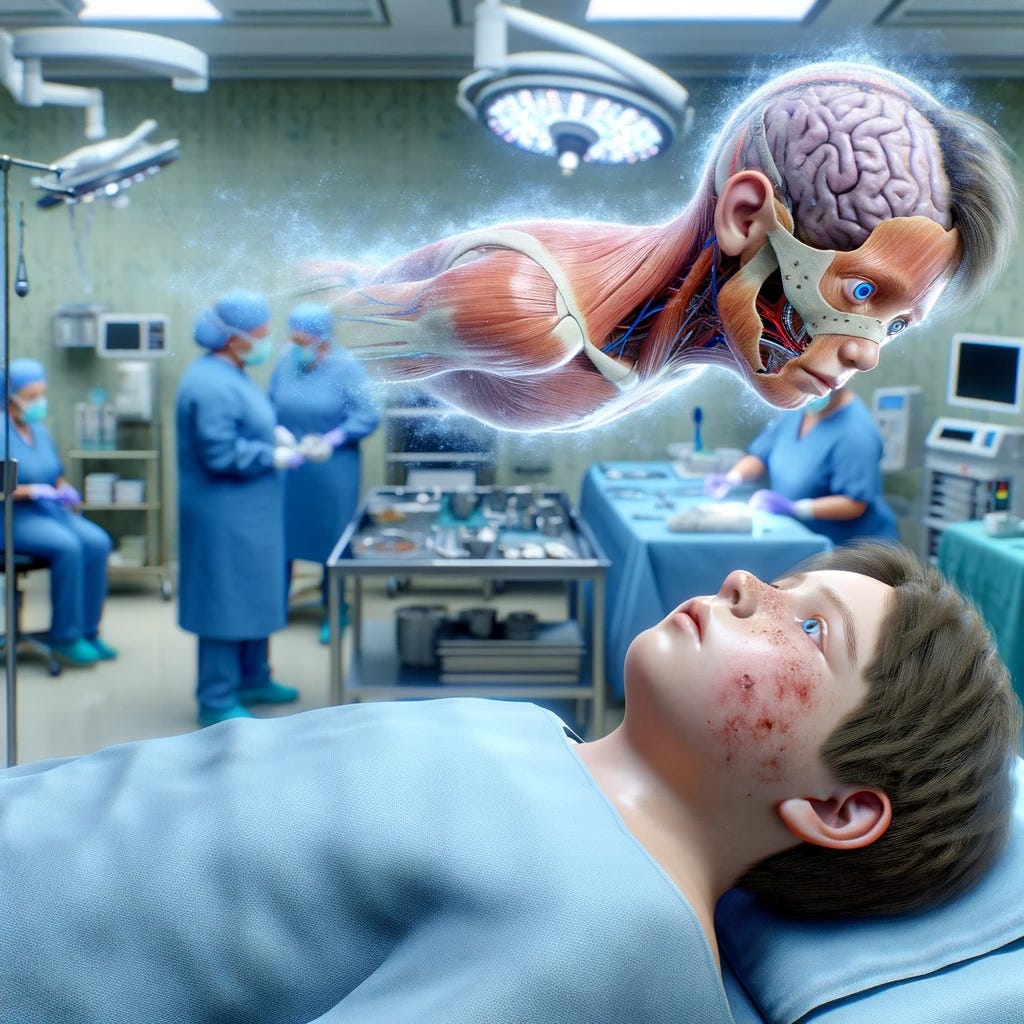

My Out-of-body experience

When I was in the hospital, at one point, I had a full-blown, honest-to-God, classic out-of-body experience: I knew that I was in an operating theatre, being operated on, and I was looking down on my body, with no real concern but with a mild interest in what was going on. However, this wasn't a religious experience. I saw no tunnel of light. No heavenly choirs of seraphim and cherubim, and no fiery damnation either. If that was dying, it wasn't so bad.

But having a duty to be rational, I can give you the logical explanation using deduction and reason - I was on significant amounts of Morphine, leading to the floating feeling. I was semi-conscious, and in shock, on the emergency operating table with an exposed brain, and I believe I was simply looking up at a reflecting surface, perhaps a surgeon's mirror. So, a drug-induced optical illusion of floating above my body, with my brain filling in the blanks.

But the time to think of death is now and daily. Not that it's a panacea: being declared dead in California was inconvenient, but unfortunately, it hasn't made me much better at keeping on top of my paperwork, and I have weekly struggles against procrastination. But I do believe If you want to have a good life, you must consider what will be a good death, for it could come at any time. Remember, you will die.

Viktor E. Frankl

References

The Conversation. (2023, May 31). How the Troubles affected healthcare in Northern Ireland. The Conversation. Retrieved November 21, 2023, from https://theconversation.com/how-the-troubles-affected-healthcare-in-northern-ireland-202892

NHS England. (2013). Independent Review of the Liverpool Care Pathway. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ind-review-lcp.pdf

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Alzheimer's Society. (2021). Statistics on dementia. Retrieved from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/news-and-media/facts-media

Dignity in Dying. (2021). Why we need change. Retrieved from https://www.dignityindying.org.uk/why-we-need-change/dignitas/

Oregon Health Authority. (2020). Death with Dignity Act Annual Reports. Retrieved from https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Pages/ar-index.aspx

Government of Canada. (2020). Medical Assistance in Dying. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying.html

Dutch Government. (2021). Euthanasia. Retrieved from https://www.government.nl/topics/euthanasia

Ng, K. (2023, February 12). Prue Leith says she supports assisted dying because her brother died ‘in absolute agony’. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/prue-leith-assisted-death-brother-b2280626.html

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man's search for meaning. Beacon Press.

* Not an actual skull, a model!